Introduction

A year has passed since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Since then, in addition to the actual conflict taking place on the ground, the two sides—those supporting Ukraine and those explicitly or implicitly supporting Russia—have been at loggerheads in various international summits.

Meanwhile, even amid this deadlock, the global environment continues to deteriorate. The United Nations Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC-COP 27), held in November 2022, aimed to finalize a rulebook for the Paris Agreement presented at UNFCCC-COP 26 the previous year and to firm the resolution to cooperate to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. The year 2022 was therefore being discussed as a time to transition from pledges to commitments.[1]

These are issues taking place on terra firma, but they are also occurring at sea, such as the waters around Japan and in the South China Sea. For this reason, in this paper, we expand on several recently published articles[2] to examine efforts to holistically transcend these issues, and provide insights to help establish and expand public opinion on maritime affairs.

Ⅰ. Ocean Governance as a Precondition for Maritime Security

Ocean governance as “comprehensive management of the oceans” is “a concept that rests on two elements: the establishment of a legal order for the management of the oceans, and the formulation and implementation of policies and action plans for the integrated management and sustainable development of the oceans.”[3]

This has been embodied in a series of initiatives, including United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982 as the legal framework in effect; the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and Agenda 21, adopted in 1992 as a plan for policy and action; the United Nations Millennium Declaration and Millennium Development Goals, adopted in 2000; The Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development, adopted in 2002; The Future We Want, adopted in 2012; and The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Sustainable Development Goals, adopted in 2015. In response to these international trends and initiatives, major powers including Japan have compiled laws and ordinances for basic policy contributing to the strengthening of ocean governance.[4]

Despite these initiatives around ocean governance advancing in parallel or complementarily both internationally and multilaterally, in reality the related issues have been dealt with unilaterally, and maritime security is reinforced where it ties directly to national interests.[5] Moreover, when examined academically, we cannot ignore the fact that there is a major disconnect between the humanities and social sciences, which generally deal with policy analysis, and the natural sciences, which engage in scientific research and studies of the ocean.[6]

Given these challenges, it must be said that, at least at this stage, both the objectives and the means of ocean governance are fragmented. Their integration is therefore a prerequisite to the establishment of comprehensive ocean governance.

Ⅱ. Integrating Maritime Security and Ocean Governance

In Japan, interest in what is discussed as “economic security” has intensified in recent years. For example, the Fumio Kishida Cabinet formed in October 2021 positioned economic security policy as a pillar of its growth strategy, and in June 2022 the Economic Security Promotion Bill (Act for the Promotion of Security Assurance through Integrated Economic Measures) was passed.[7] Initiatives such as these remain on the rise, such as with the launch of the Key and Advanced Technology R&D through Cross-Community Collaboration Program (K Program) under the auspices of the Council for Economic Security Promotion and the Committee for an Integrated Innovation Strategy. The Cabinet Office, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, and the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry also play central roles in promoting advanced research and development for national economic security on a cross-ministerial basis, taking the specific form of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO), which will serve as the organizations responsible for managing and operating the program fund and for promoting research and development through this program.

In the early stages of the Cold War, NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) and the Marshall Plan (European Recovery Plan) were established and put into operation in the West, while the Warsaw Pact and COMECON (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) were established and put into operation in the East, closely tying security to economic growth.[8] These approaches testify to the historically close relationship between security and economic growth.

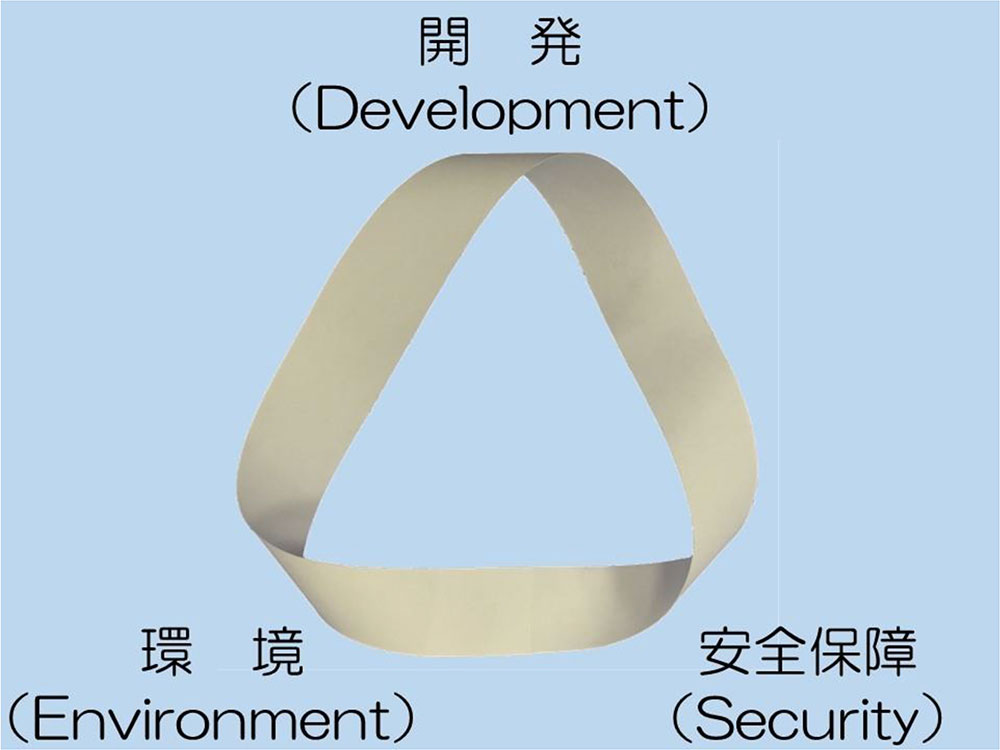

This trend is also evident in maritime security initiatives. Meanwhile, environmental conservation, touched on at the beginning of this paper, is a pressing issue we cannot ignore. Moreover, selective prioritization of these issues is unadvisable; rather, all must be addressed in tandem. For this reason, from the perspective of promoting maritime policy and establishing ocean governance, we can view the relationship between national security, economic growth, and environmental protection as a trilemma [Figure 1].[9]

This trilemma has grown increasingly complex in recent years, and it has become apparent that security, economic growth, and environmental preservation are not separate themes but closely linked that must be addressed holistically. For example, economic growth with environmental protection is becoming a specific theme in discussions on a sustainable maritime economy, i.e., the “blue economy.”[11] Environmental protection and security is similarly becoming a specific theme, alongside what has been called “climate security,” i.e. responses to intensifying wind and flood damage caused by climate change.[12] Economic growth and security must therefore also be addressed jointly.

III. Sustainability in Maritime Security

Themes related to economic growth and security in the maritime sector include, for example, conflicts over seabed mineral resources at various levels,[13] conflicts over resources in exclusive economic zones following the establishment of UNCLOS,[14] and, more recently, BBNJ (Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction) is also becoming a topic related to economic growth and security in terms of genetic resources.[15]

These topics have a theme in common of the struggle to obtain limited resources. As a result, they tend to involve the use of force, sometimes including the deployment of military forces. Use of the term “limited” above also includes “effective use of limited resources.” The key question in dealing with security based on economic growth is therefore how to ensure sustainability.

Past discussions on ensuring stability have often focused on target resources. It should go without saying, however, that the most important aspect would be the safety of the people involved, for example, in search and rescue (SAR). Moreover, SAR-related efforts is a field that is expected to transcend any conflicts between the affected countries. In fact, Japan and the former Soviet Union concluded the Japan-USSR Sea Rescue Agreement in 1956, showing that even during the Cold War era, with its various strained relationships, collaboration from a humanitarian standpoint was possible.[16] On the other hand, changes in the maritime environment due to climate change could lead to the expansion of IUU fishing (illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing), which has thus far primarily been an issue in the South Seas, the Arctic Ocean, and elsewhere.[17] For this reason, law enforcement actions against IUU fishing and other illegal activities are also efforts essential to ensuring sustainability.

Conclusion: Aiming to Contribute to Sustainable Ocean Governance

As noted above, the goal of ocean governance is to safeguard our oceans. Holistic efforts are therefore needed, which take into account not only maritime security, which constitutes or forms the basis of ocean governance, but also the maritime economy and environment. These efforts may seem closer to “human security” than maritime security. However, fully resolving the various issues maritime security is currently facing with efforts based on traditional security perspectives is challenging. For this reason, we hope that the perspectives and findings presented in this paper will reveal new forms of ocean governance, and foment the establishment and expansion of public opinion on these topics leading to new maritime security models that transcend these issues.