Introduction

Fishing and seafood processing industries are susceptible to changes in international affairs. Indeed, this is one of the reasons why Japanese fishing vessels are having difficulties operating in the northern territories due to Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine.

In June 2022, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs notified the Japanese government that it would temporarily suspend safe fishing operations (implementation of the agreement), which had been underway in accordance with the “Framework Agreement for the Operation of Japanese Fishing Vessels in the Waters Surrounding the Northern Territories,”[1] until Japan fulfills all of its financial obligations, citing Japan’s delay in finalizing the paperwork related to the provision of free technical assistance to the Sakhalin Oblast and the freezing of payments that were due under the agreement.[2]

According to Tetsuro Nomura, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan, intergovernmental negotiations concerning this agreement had not advanced even by January 2023 because [3] In response to this impasse, the Fisheries Agency of Japan has proposed measures to support fisheries in the surrounding area. Evidently, Russia’s diplomatic influence over Japan’s fishing industry persists.

Within the fishing and seafood processing industries, offshore fisheries are particularly vulnerable to changes occurring in international affairs. Offshore fisheries constitute a “border industry” that occasionally carries out operations in close proximity to national boundaries. As such, it represents a key economic activity at the forefront of Japan’s international relations. Consequently, any shifts in the relationship between Japan and the neighboring countries can directly impact this industry.

In March 2022, soon after the invasion of Ukraine, Jiro Kanekohara, then Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, made a statement during a meeting of the Budget Committee of the House of Councilors that succinctly expressed this. Specifically, he advised caution in waters associated with Russia, stating that “in the past, even a brief entry into the waters has resulted in capture. This time, we advise caution, as the danger is even greater.” He candidly urged fishermen to exercise restraint in their operations, warning that “if you take even one step into the area, you will be arrested by the authorities from the other side.”[4]

Japan is close to China and Russia, two major “fishing powers,” as well as Taiwan, which also has a significant presence in the global fishing industry. South Korea and North Korea are also in competition with Japan in their operations in the Sea of Japan. Given the sensitive nature of the fishing industry to international affairs, it is becoming increasingly necessary to examine and analyze the fishing industry in Japan and its neighboring countries to establish a maritime order.

The present paper focuses on the East China Sea, where China’s maritime expansion continues, and provides an overview of the current state of the Japanese fishing industry. Furthermore, it examines the industry’s role and function in relation to the multifaceted development of the maritime order.

I. The decline of Japan’s fishing industry and concerns over food security

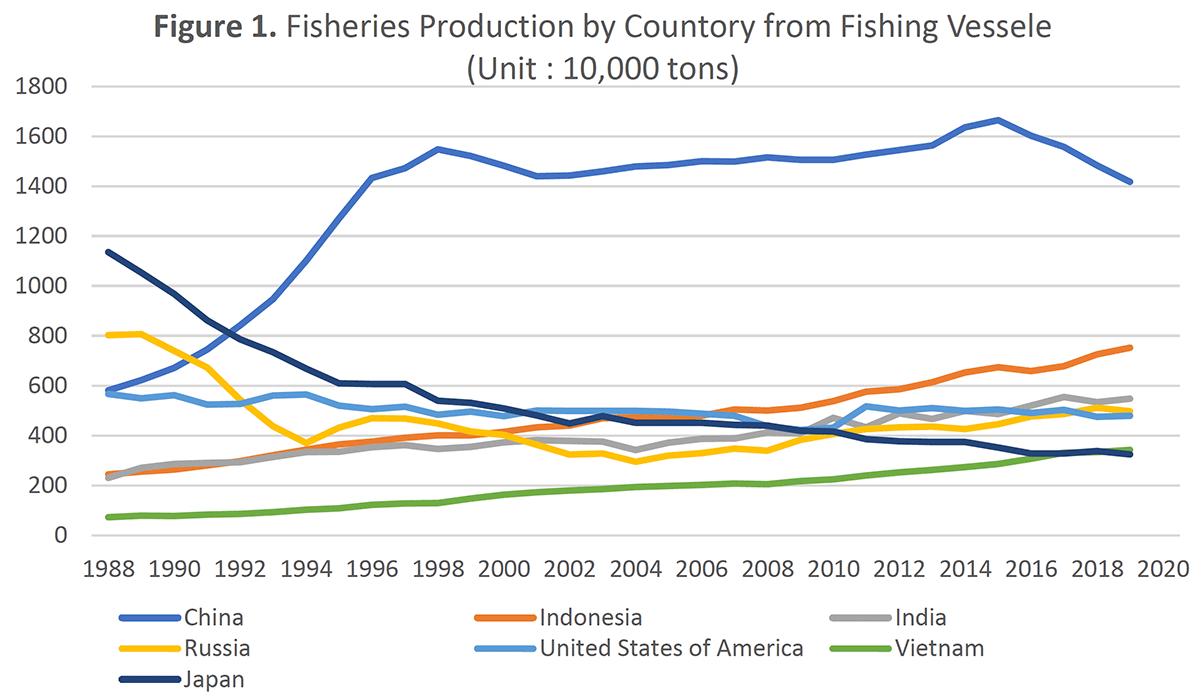

Based on the data compiled by the Fisheries Agency,[5] it is evident that the Japanese fishing industry, which once boasted the largest production volumes in the world, has been consistently shrinking (refer to Chart 1). The persistent decline of the Japanese fishing industry can be attributed to the loss of fishing grounds in the North Sea and high seas due to the establishment of the 200-mile limit and the reinforcement of resource management systems, which has resulted in the decline of critical forces such as far-seas bottom trawling fisheries. Although the offshore fishing industry had remained stable due to abundant catches of Japanese pilchards, it was inevitably impacted by resource fluctuations inherent to the industry, leading to a challenging business environment with limited prospects for a reversal.

While Japan’s fishing industry has been in decline, the rapid expansion of China’s fishing industry since the 1980s has been noteworthy. Currently, the production volume of Chinese fisheries from their fishing vessels greatly surpasses Japan’s 3-million-ton level. Although there are indications of a recent plateau, it is undeniable that China maintains a dominant fishing industry that eclipses other countries.

Since 2000, Japan has been surpassed by emerging powers such as Indonesia, India, and Russia, a traditional fishing nation. A steady expansionary trend can also be observed in Vietnam’s fishing industry. The contrast between the growth of these emerging powers and the decline of Japan’s fishing industry has become increasingly pronounced.

Due to a decline in production and shifts in consumption patterns, Japan’s self-sufficiency rate for marine products (edible seafood by weight) has experienced a downturn since peaking at 113% in fiscal 1964. It currently fluctuates between 50%-60%, with a confirmed rate of 57% for the fiscal year 2020.[6] These figures are so grim that they obscure the history of Japanese fisheries as a prominent export industry.

Consequently, Japan has resorted to importing a substantial quantity of marine products to satisfy its domestic demand. In the fiscal year 2021, the total import value of seafood such as salmon, trout, skipjack tuna, other tuna varieties, and shrimp amounted to 1.6099 trillion yen.[7]

China is the biggest supplier of for Japan, comprising 18.0% of the total marine product imports. Chile and Russia rank second and third, with 9.2% and 8.6%, respectively. In addition to paying China a substantial sum of 290.4 billion yen, Japan faces the reality that two of its top three marine product suppliers are also countries that present security concerns. It is crucial to acknowledge the importance of food, including seafood, as a vital commodity for the Japanese population.

Ⅱ. Inferiority in the East China Sea and the new Japan-China fisheries agreement

The contraction of the Japanese fishing industry is evident in the fishing grounds surrounding Japan. In the East China Sea and the Sea of Japan, there is competition from Chinese and South Korean fisheries. In the Sea of Okhotsk and around the northern territories, relations with Russia have been strained due to sudden seizures and on-site inspections, leading to the deterioration of operating conditions. Recently, an expansion of Taiwanese fishing activity has been observed in the southern part of the East China Sea, particularly around the Senkaku Islands. Thus, various factors have compounded, perpetuating the decline of Japan’s fishing industry.

The diminished presence of Japan in the East China Sea has been viewed with grave concern, given the rapid expansion of Chinese fishing operations. According to data from the Japan Far-Seas Purse Seiner’s Association, the of large- and medium-size purse seine fleets, which primarily operate in the East China Sea, have decreased from 386,000 tons across 64 fleets in 1989 to 114,000 tons across 20 fleets in 2018.[8]

The state of the bottom trawl fisheries operating in the waters west of Japan is even more severe. Due to a government ordinance that restricts the permitted fishing area to the west of 128°29’53” E longitude, the options for fishing grounds are limited. Consequently, competition with Chinese fishing vessels became inevitable, leading to a decline in the industry. In contrast to the 1960s, when around 800 vessels caught approximately 350,000 tons of fish, only 8 vessels (4 fleets) remained in 2020, catching about 3,200 tons per year.[9]

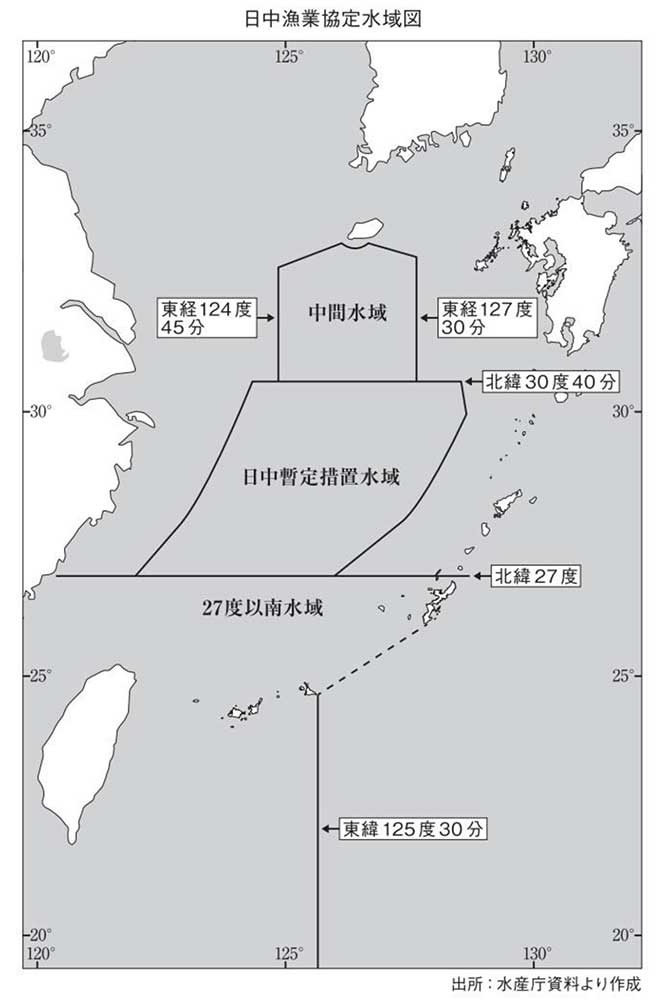

The diminished presence of Japan’s fishing vessels; operations in the East China Sea fishing grounds can be attributed, in part, to the ratification of the new “ Fisheries Agreement,” which broadly recognized the flag state principle and facilitated the expansion of China’s presence in the waters. From the perspective of the Japanese fishing industry, the new pact established the “Provisional Measures Zone,” “Intermediate Zone,” and “Zone South of 27 Degrees North Latitude,” which had the detrimental effect of preventing the establishment of exclusive economic zones throughout almost the entire East China Sea (see Figure 2).

The severity of the situation was highlighted in the May 2013 National Diet. During a meeting of the House of Councilors Committee on Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, the then-minister Yoshimasa Hayashi mentioned that in 2011, Japan’s landings in the provisional measures zones of the East China Sea reached 38,278 tons, while China’s landings were overwhelmingly larger at 1.7 million tons.[10]

According to the Government of Japan, “China does not recognize any of Japan’s claims to the median line”[11] pertaining to the boundary between their exclusive economic zones in the East China Sea. Consequently, despite the need for a mutual agreement between the two countries to establish the boundaries, “the demarcation of the exclusive economic zones and continental shelf in the East China Sea is still pending.”[12]

Be that as it may, it is important to “exercise sovereign rights and jurisdiction following international law within the waters extending to the median line until the boundary is established” and “to assert Japan’s entitlement to an exclusive economic zone and continental shelf extending 200 nautical miles from the baseline of its territorial sea.”[13]

The new “Japan-China Fisheries Agreement” fails to adequately address such vital claims. In order to sustain Japan’s fisheries production and fishing fleets, it is imperative that efforts be made to address issues with a long-term perspective in mind.

III. The shifting “borders” in the East China Sea

China’s maritime presence in the East China Sea has expanded since around 2000. Incidents surrounding the Senkaku Islands have occurred frequently, including illegal arrivals on the Senkaku Islands by activists and operations by Chinese naval vessels and ships from the China Coast Guard.

Taiwan also strengthened its territorial claims to the Senkaku Islands under the Ma Ying-jeou administration. In August 2012, Taiwan announced the “East China Sea Peace Initiative,” based on the premise that the “Diaoyutai Islands” are affiliated with Taiwan, and proposed joint development of resources in the East China Sea. Furthermore, as there have been moves toward collaboration between Taiwanese and Chinese (Hong Kong) “Diaoyu activists,” the Japanese government has grown increasingly apprehensive about the potential for Sino-Taiwanese cooperation regarding the Senkaku Islands dispute.

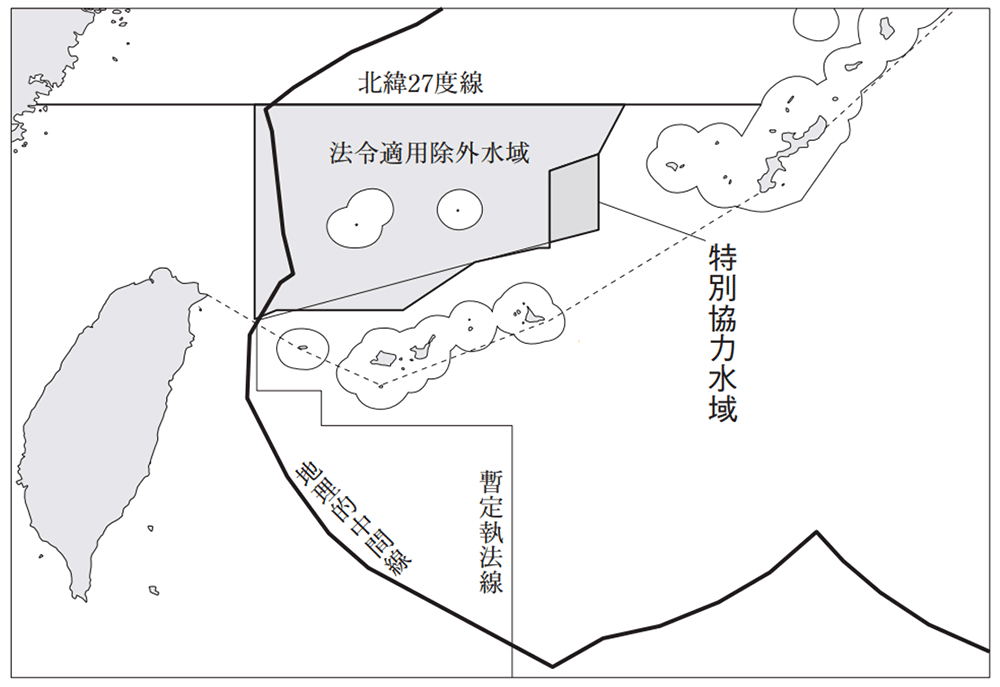

One measure to dispel the accumulated concerns between Japan and Taiwan was the ratification of the “Japan-Taiwan Private Fisheries Agreement”[14] in April 2013. Despite being labeled as a “private fisheries agreement,” it functioned similarly to other fisheries agreements, such as the “Japan-China Fisheries Agreement” and the “Japan-Korea Fisheries Agreement,” through the amendment of the enforcement ordinance that accompanies Japan’s “Fishery Sovereignty Act” (Act No. 76 of 1996).[15]

In essence, Japan refrains from applying Articles 5 through 13 of the aforesaid act to individuals listed in the Taiwanese family register within two designated areas: “exempted waters” and “special cooperation waters,” which surround the Senkaku Islands south of 27 degrees north latitude [refer to Figure 3]. In addition, Japan permits “fishing, harvesting or exploration of aquatic animals and plants” without the need for authorization or payment of a fishing fee.

The agreement permits both Japanese and Taiwanese fishing vessels to operate within two designated water zones on a flag-state basis, akin to the “Provisional Measures Zone” established under the new “Japan-China Fisheries Agreement.” This effectively grants Taiwanese fishermen access to Japan’s exclusive economic zone (fishing grounds). It can be inferred that the fisheries agreement serves a diplomatic function by preventing collaboration between China and Taiwan on the issue of the Senkaku Islands through concessions made to Taiwan in the fisheries sector.[16]

However, Japanese fishermen, particularly those from Okinawa and Miyazaki prefectures, strongly opposed the decision to allow Taiwanese fishermen access to their fishing grounds. Alas, this was not realized. Furthermore, the assembly strongly protested against both the Japan-China Fisheries Agreement and the Japan-Taiwan Fisheries Agreement and called for their review because they would inflict significant harm on fishermen’s safe operations and livelihoods.

The citation of the “Japan-China Fisheries Agreement” in the aforementioned resolution has led Japanese fishermen operating in the East China Sea to understand that this represents the second instance of losing their fishing rights, which resulted in a significant impact.

In August 2022, China conducted “critical military exercises” near the waters legally exempt from the Japan-Taiwan Agreement. Yonaguni Island’s fishermen were forced to suspend their operations due to missile launches from the continent, some of which landed in nearby waters.[17]

The current state of affairs surrounding the fisheries in the East China Sea indicates that initiatives to prevent the diminution of Japan’s interests in the region, such as protecting its exclusive economic zone, are anticipated.

Conclusion

The Japanese fishing industry faces a number of challenges that must be addressed in conjunction with the underlying diplomatic issues. These include a chronic shortage of human resources[18] and the depletion of fishing villages (communities behind fishing ports)[19] that have historically supplied human resources, which are examples of the vulnerabilities that have accumulated within the industry.

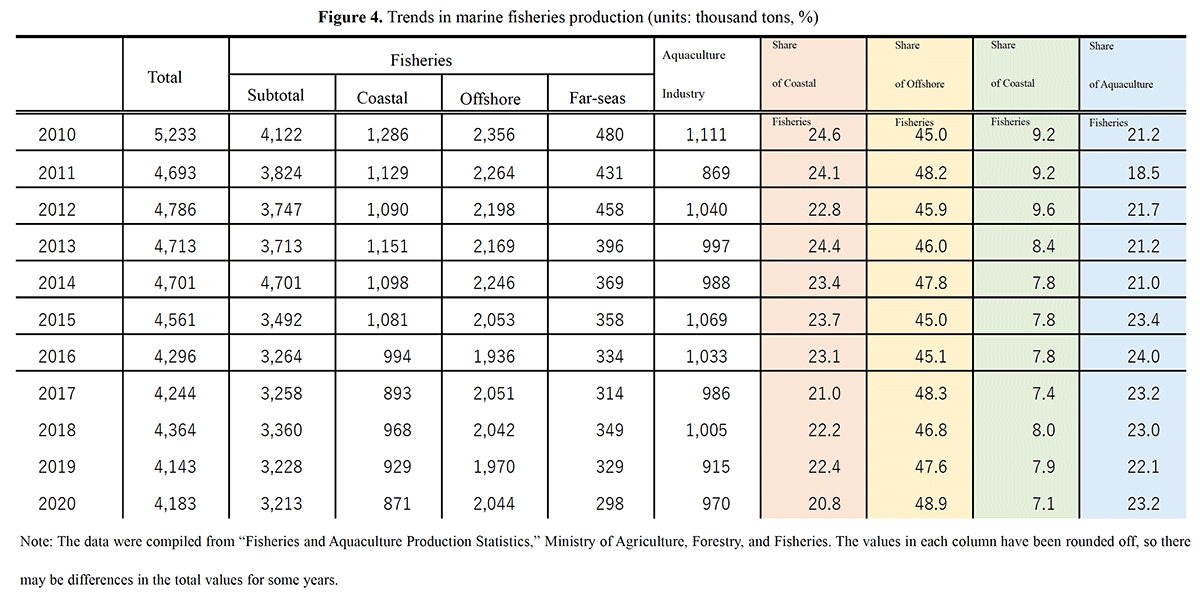

Japan’s offshore and far-seas fisheries remain a significant source of food supply, accounting for over 50% of the country’s total seafood production from marine sources (refer to Figure 4). The maintenance of this “border industry” is an issue that cannot be ignored from a security standpoint. Naturally, as “fishing powers” such as China and Russia strive to maintain or expand their influence, this could serve as an important perspective in contemplating the multifaceted development of maritime order in the waters surrounding Japan.

The East China Sea remains a significant fishing ground for China’s fishing industry, which boasts the world’s largest fleet of fishing vessels. This industry continues to adversely impact Japan’s mainstay bottom trawling and purse seine fisheries. The northward expansion of Taiwanese fishing vessels within the waters that fall under the Japan-Taiwan Private Fisheries Arrangement cannot be ignored. In the Sea of Okhotsk and the North Pacific Ocean, Russia’s tangible and intangible pressure on Japanese fisheries has become increasingly evident following its invasion of Ukraine, as earlier discussed.

Japan’s fishing industry currently lacks the capacity to cope with all of the deteriorating external conditions, including diplomatic factors. In the era of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, securing stable fishing grounds such as exclusive economic zones is a national mission, not a responsibility that should fall solely on individual fishing operators.

In this context, it is crucial to consider the development and expansion of public opinion on marine issues. For the fishing industry, this will foster an environment that encourages the reevaluation of the industry’s r significant value to the public.

The Japanese fishing industry is currently in decline, and the concerns of fishermen are struggling to reach the general public and political spheres. Despite this, the Japanese fishing industry remains an essential sector for national security, as it provides vital food resources to the population and maintains industries along the fringes of the sea or “borders” of Japan. Together with fishing villages, it also contributes significantly to preserving Japan’s vast coastal regions and numerous remote islands.

Ultimately, it is essential to foster public understanding and sympathy for the industry’s significant public nature to sustain the Japanese fishing industry, which plays a crucial role in supporting the “multifaceted development of the maritime order.” The development and implementation of concrete measures to achieve this objective are eagerly awaited.

References

Editorial Board. The Encyclopedia of Contemporary Geopolitics. Maruzen Publishing.

January 2020