Introduction

I interpret this discussion of the “creation and expansion of maritime ‘public opinion’” as implicitly assuming the “strengthening of Japan’s (government’s) voice in maritime affairs” towards “foreign governments,” “inside international organizations,” and “the people behind foreign governments.”

The Japanese government’s statements, as long as Japan is a democratic country, must be based on the intentions of people residing in the territory of Japan (including those who do not necessarily have Japanese nationality) or legal entities established under Japanese law. My area of responsibility is marine navigation. When speaking of marine navigation, I refer to the route of activity of merchant vessels.[1]

As a nation ruled by law, the Japanese government’s actions are based on the law. It goes without saying that the element of “nationality of an object” is important with respect to the law enforcement pertaining to that object.

Ⅰ. Merchant Vessels and Nationality

1.Operation of Merchant Vessels and Nationality

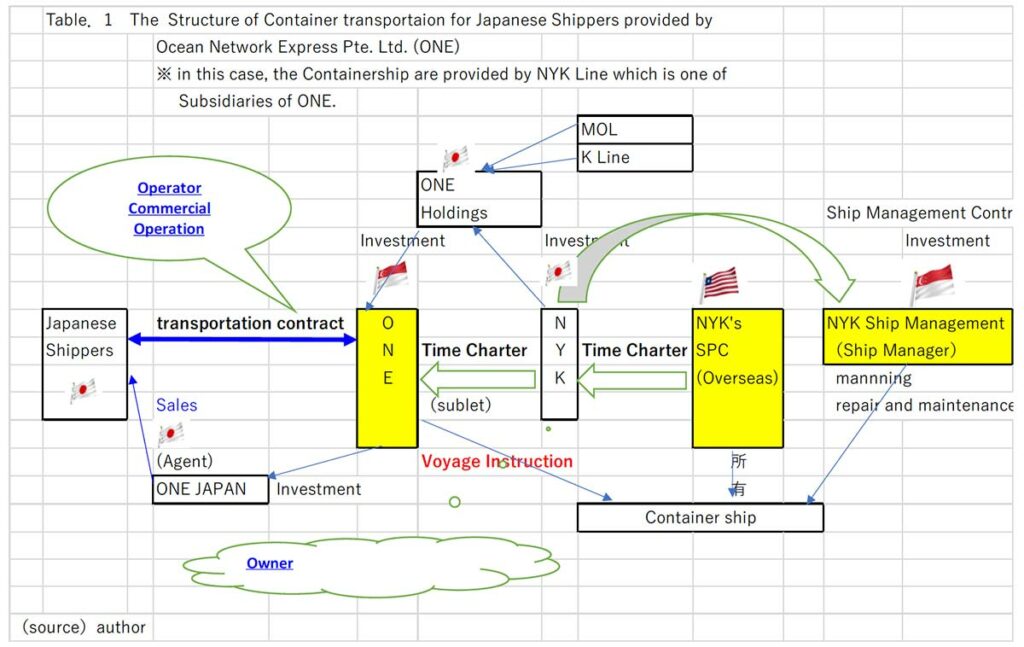

The operator of a merchant vessel earns revenue and profits by providing cargo or passenger transportation services using a ship (merchant vessel) to cargo shippers and passengers, for which the operator receives compensation. The operator gives sailing instructions to the ship to carry out the transportation actions of the ship.

Historically, operators have engaged in supplying transportation services by providing ships that they themselves own. However, it is now common for operators to charter vessels owned by others under chartering agreements to provide tra―nsportation services. In practice, the entity that owns a ship is called the “owner” as the antonym for “operator.” Legally, the owner is called the “shipowner” and the operator is called the “charterer.”

When an owner charters a ship out to an operator, the ship is often chartered with a crew on board and ready to operate it at any time (time charter). The term “ship management” refers to the hiring of seafarers, assigning them to a ship in an employment relationship, and requiring them to perform maintenance so that the ship is ready for operation at any time.

Traditionally, ship management was a business that shipowners handled themselves, but since approximately the 1970s, for various commercial reasons, shipowners have entrusted ship management to third parties – ship management companies that are independent of the shipowner, and, in many cases, the shipowner merely owns the ship as an asset. In short, shipping companies are now separated (unbundled) into separate legal entities for each of their functions with respect to transportation by ship, ship management, and ownership of ships (asset investment).

The operational configuration of a merchant vessel is shown below (Table. 1).

This is a case study of a Japanese company that provides marine container transport using containers. Container transport was chosen for this case study because Japan’s exports of industrial products and imports of daily commodities that support the consumer lifestyles of Japanese citizens are transported by containers.

What is important here is that the shipping company has been unbundled into operator, owner, and ship management company and that each of these legal entities chooses the country and nationality in which it is incorporated for its commercial operations. This is normal for shipping companies everywhere (including Japan). Shipping companies are generally understood to be the entities that undertake cargo and passenger transport from shippers and receive compensation (freight charges and charter fees) to earn profits. The ship responsible for the carriage may be different from the country in which the shipping company was incorporated as a company because the ship responsible for the carriage may be owned by a foreign subsidiary established by the same shipping company. This type of a ship is called a flag-of-convenience ship, which is also common globally.[2]

In reality, what is commonly referred to as a “Japanese shipping company” may be nothing more than an “absentee owner” in Japan that merely controls the capital of an operator or ship management company established outside of Japan. In the case of container transport, this is precisely the situation. The entity that owns the ship, the entity that manages the ship, and the entity that manages the operation of the ship and gives sailing instructions to the ship are all foreign corporations.

This is reflected in the fact that the Japanese market is no longer the main business battlefield for Japanese container shipping companies, as evidenced by the fact that the breakdown of freight revenues (2021) from container transport by Japanese shipping companies is as follows: exports, 190.8 billion yen (9.4%); imports, (7.8%); and tripartite transport, 1.6878 trillion yen (82.8%).[3]

2.Entities and Goods Related to Merchant Vessels and Their Nationalities

With respect to ships and the entities/goods related to ships that are used for voyages for commercial purposes (i.e., for the purpose of earning revenue and gaining profit by means of operating ships), there are entities and goods that have various levels of “nationality” (Table. 2).

It is important to note that, although a ship is physically a movable asset, each ship is individually managed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) from the completion of its construction until after it is dismantled, with a serial number called an “IMO Number”[4] and a unique name and nationality. It is an anthropomorphic entity, so to speak.

The ship’s nationality creates a relationship between the coastal state and the flag state when the ship is in the territorial or inland waters of a foreign country, and the flag state maintains order when the ship is on the high seas. The latter is accomplished through enforcement of the law by the country of registry on the ship and the people on board.

However, the situation is different for Japanese cruise ships. All cruise ships operated by Japanese shipping companies are registered in Japan,[5] with the exception of the passenger ship (Panamanian registry) chartered by Peace Boat (an international NGO) and its related travel agency,[6] and all operators, owners, and ship management companies are Japanese corporations. The reason is that the Japanese domestic cruise service is a Japanese coastal shipping service, which is subject to the cabotage system and requires that the ship be of Japanese registry.

Conversely, since the Peace Boat Center is an organization that aims to promote international exchange, it has a poor track record in organizing domestic cruises.

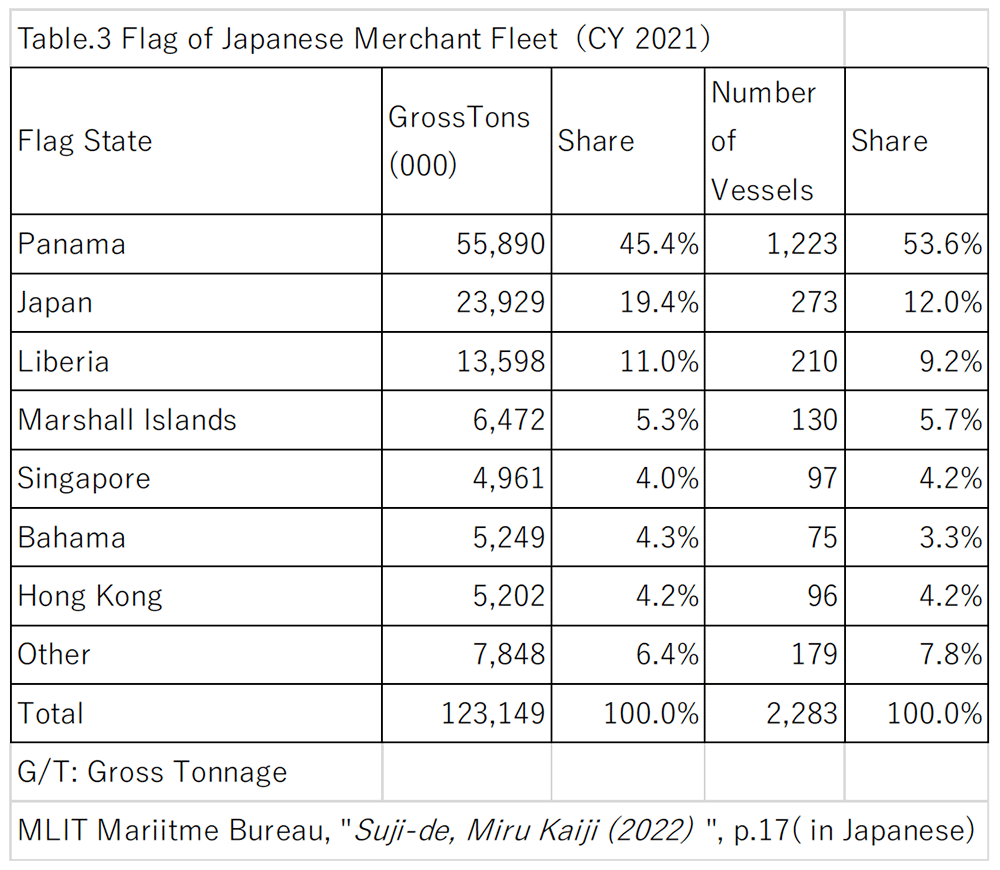

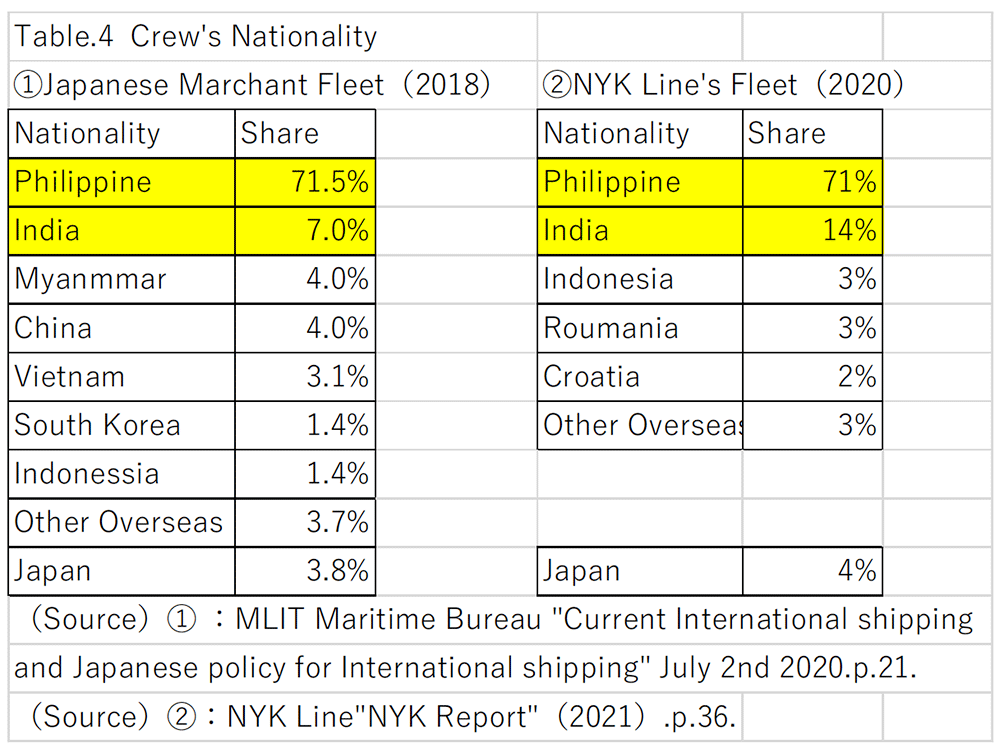

Incidentally, Table. 3 shows the nationalities of the vessels in the Japanese merchant fleet (ocean-going vessels operated and managed by Japanese shipping companies)[7] and Table. 4 shows the nationalities of the crew members on board. In short, many of the ships in the Japanese merchant fleet are registered in countries such as Panama, Liberia, the Marshall Islands, and Singapore, and many of the crew members are Filipinos and Indians. These are the results of economic rationality. Additionally, the problem of seafarers includes the fact that few young Japanese people seek employment as seafarers.[8]

Ⅱ. Shipping Route and Nationality of Merchant Vessels

This section discusses shipping routes and the nationalities of merchant vessels.

1. Shipping Routes and Ocean Areas

Let us consider the ocean areas in which a merchant vessel navigates its route from when it departs a port in Japan to when it arrives at a port in a foreign country. First, the Japanese port is in “inland waters.” Merchant vessels departing from inland waters pass through Japanese territorial waters and enter the high seas. Also, to enter a foreign port, a ship enters the inland waters containing the port from the high seas, through the territorial waters of the foreign country where the destination is located, and completes the voyage by arriving at the port.

Merchant vessels might sail through the territorial and inland waters of a third country before leaving the high seas to enter a foreign port after departing from Japan. When navigating in the territorial waters of a third country, there is no obstacle to the merchant vessel as long as it is navigating harmlessly. If the territorial waters of a third state are “international straits,” it is sufficient to exercise the right of transit and navigate through them swiftly.

After leaving Japan and before entering a foreign port at the destination, the vessel may pass through inland waters without the purpose of calling at a third country’s port.

For example, the Seto Inland Sea is an inland body of water to begin with, and if a ship were to proceed from Hong Kong to northern Vietnam (e.g., Haiphong), the shortest route would be through the strait between the Leizhou Peninsula and Hainan Island on the Chinese mainland, which the Chinese government claims is China’s inland water and requires payment of a fee for the passage of non-Chinese-flag ships. If this were undesirable, it would then become necessary to give up navigating the straits and bypass them using the waters off the southern coast of Hainan Island.

Alternatively, sailing the Northern Sea Route requires obtaining prior permission from the Northern Sea Route Administration of the Government of the Russian Federation, but there are waters along the way (Vilikitskiy – Strait and Sannikov Channel) that Russia claims as inland waters.[9]

If the ship’s country of registry considers these claims by the coastal state to be unjustified, then the country of registry must stop the registered owner from complying with the coastal country’s domestic law requirements for navigation in the waters in question. In short, they must order the registered shipowner “not to pass through such waters.”

2. Cases in Which the Nationality of a Merchant Vessel Is an Issue on a Route

Foreign merchant vessels are free to pass through the territorial waters of the coastal country as long as they pass without harm, so the territorial waters belonging to the country in which they navigate are not in themselves a problem. For example, if there are islands whose territorial rights are disputed by the countries concerned, there is no reason for foreign merchant vessels to know which country effectively controls the islands unless they are prevented from exercising their right of innocent passage by the coastal country.

However, it is a different story when a coastal country enforces its laws against foreign merchant vessels based on one of their domestic laws. From the point of view of the ship’s country of registry, the shipowner’s acceptance of the coastal country’s law enforcement is regarded as an endorsement of the domestic law of the coastal country by a private person (legal entity) of the ship’s country of registry.[10]

In some cases, this may be an undesirable practice in terms of the value judgment of the ship’s country of registry.

Specifically, if a certain country claims to have effective control over an island, but the legitimacy of that country’s effective control is disputed and the ship’s flag country does not recognize that effective control, the shipowner, a private person (legal entity) of the flag country, must perform the procedures to enter the port required by the domestic law of the country that has effective control over the island to bring the ship into the port of the island.

However, if a ship (e.g., a Panamanian-registered ship) is chartered by an operator that is a legal entity (e.g., Japanese shipping company) from a country different from the ship’s country of registry (e.g., Panama), and the vessel enters a port on an island (the so-called Northern Territories) in the country that effectively controls the island (Russia) and performs the procedures to enter the port (subject to Russian domestic law), it can be said that it is the shipowner of the ship in the country of registry (private individual or legal entity of Panama) that is subject to the domestic law of the island of the country (Russia) that claims effective control, not the operator (Japanese legal entity).

It is an international custom for merchant vessels to fly the flag of the destination country (destination flag) on the highest point of the ship (radar mast) while traveling. If a ship entering a port in an area where there is a dispute over ownership flies the flag of the country that effectively controls the area, the fact remains that the legal entities and private citizens of the ship’s flag country have not denied effective control of the area.[11]

In this respect, it could be said that the use of flag-of-convenience ships could be seen as a device to automatically ensure that the entity that substantially controls the vessel will not carry out commercial activities that are inconsistent with the foreign policy of the country to which it belongs (even if the subject concerned is not explicitly aware of this fact).

Therefore, one option would be to intentionally have the shipping company use a flag-of-convenience ship to show awareness of the issue and avoid engaging in commercial activities that are not consistent with the foreign policy of the coastal state of the country to which it belongs.

Some specific examples are as follows:

In Japan’s neighboring waters, there is direct cross-strait shipping between mainland China and Taiwan, but at present only mainland Chinese and Taiwanese shipping companies are allowed to participate in this direct cross-strait shipping. The ships used for these cross-strait crossings are not operated by mainland Chinese or Taiwanese shipping companies, and they are neither Chinese- nor Taiwanese-registered vessels but are flag-of-convenience vessels.

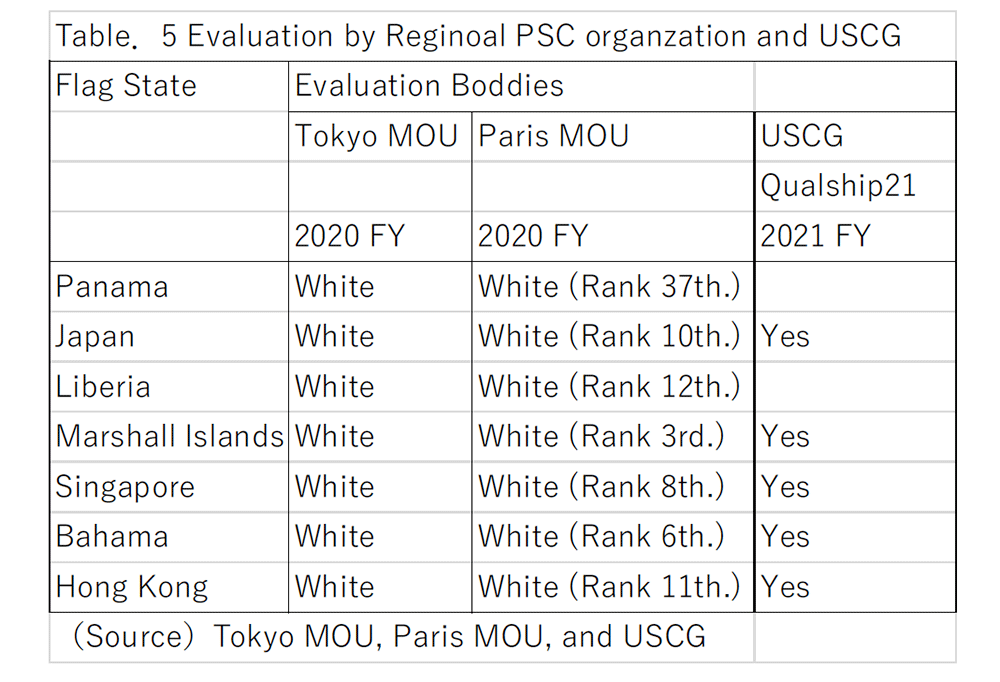

It should be noted that the fact that a ship is registered under a flag of convenience does not imply that the quality of the ship or crew is low, provided that the ship’s country of registry has been chosen with care. At least we know that the country of registry chosen by Japanese shipowners belongs to the higher-quality end of the spectrum. The IMO has a system in place whereby the port-of-entry country sends officials to inspect foreign vessels entering the port for compliance with the IMO conventions (such foreign ship inspections are called Port State Control, or PSC).[12] The results of these inspections are tabulated for each flag state, and countries with good compliance with treaties are white-listed or certified as good (by the U.S. Coast Guard) (Table 5).

III. Flag Country and Japan

Summary of the Discussion in I & II

If the goal is the “strengthening of Japan’s (government’s) voice in maritime affairs towards foreign governments, inside international organizations, and the people behind foreign governments,” what measures should the Japanese government adopt in relation to the shipping routes of merchant vessels? As noted earlier, the concept of nationality is important in considering this issue.

First, in terms of nationality, an issue that provides an easy comparison is that of international cruise ships operated by Japanese shipping lines. These are operated by legal entities established under Japanese law, most of their passengers are Japanese, and their vessels are registered in Japan. These international cruise ships allow large numbers of Japanese people to visually inspect maritime issues along the route. This is done upon request to the ship operator to plan a cruise that will allow the ship to sail through area that is of concern to the Japanese government, as in the case of viewing a remote Japanese island from a distance. In fact, Asuka II, belonging to and operated by NYK Cruises Co., Ltd., sailed off the coast of Okinotorishima Island on its return trip around the world in 2014, with passengers on board taking in a distant view of Okinotorishima.[13]

Second, in terms of cargo transport, it is an undeniable fact that most of the Japanese merchant fleet vessels are registered as flag-of-convenience ships due to economic reasons.

If this is the case, we must begin our considerations with this fact.

Are the countries where Japanese shipping companies choose to register their ships (Panama, Liberia, Marshall Islands, Singapore, the Bahamas, and Hong Kong) potential partners (in the sense of having the same or similar orientation) in terms of diplomacy carried out by the Japanese government? Is this not the case? Alternatively, consideration could be given to whether some of the countries and regions (such as Cyprus and the Isle of Man) where foreign shipowners choose to register their ships could be potential partners.

This is only an introduction to this discussion, but we can consider the following examples:

- The Marshall Islands could be considered a potential partner of Japan in terms of diplomacy since it has the framework of bilateral relations with the United States in terms of defense and diplomacy.

- In terms of international trade, Singapore and Japan already have a deep relationship, having concluded an EPA (Japan and Singapore for a New Age Economic Partnership) at the government level quite a while ago (2002). At the private-sector level, Singapore is also a country that Japanese shipping companies utilize not only as a country of registry, but also as a country of establishment for local subsidiaries and companies engaged in ship management that are regional headquarters for cargo sales and head office functions for ship operation and management.[14]

- Dialogue with Panama in terms of the host and user countries of the Panama Canal has already been established.

- On October 3, 2011, Nippon Kaiji Kyokai (Class NK)[15] concluded a strategic partnership agreement[16] with Liberia (strictly speaking, LISCR, an operating company authorized by the Liberian government to act as an international ship registry agent) in the area of ship technology, which continues to this day.

Proposals

- I propose that the Japanese government request that international cruise ship operators in Japan, in planning the voyages of their vessels, choose routes through waters where Japanese passengers will be exposed to maritime issues.

- I propose that the Japanese government build a relationship with flag-of-convenience countries as partners who share the same maritime ideals.

End