Introduction

Among the strategic approaches prioritized in the National Security Strategy, revised in December 2022, are stronger initiatives aimed toward the seamless protection of Japan across all fronts. There are nine specific items: 1) cybersecurity; 2) maritime security and coast guard capacity; 3) space security; 4) improving and actively utilizing technological capability related to security; 5) improving intelligence capability; 6) strengthening Japan’s domestic ability to sustainably respond to emergencies; 7) strengthening systems for the protection of citizens; 8) protecting Japanese people living overseas, etc.; and 9) securing the energy and food resources essential to national security. All these issues are of extreme importance and must be tackled urgently.[1]

With regard to maritime security and coast guard capacity, the Strategy mentions initiatives to secure freedom and safety of navigation, and overflight, and to maintain and develop international maritime order based on universal values including the rule of law. These initiatives include surveilling maritime conditions in sea lanes; strengthening multilateral maritime security cooperation through joint drills, exercises, and port visits; securing safety for marine traffic through anti-piracy measures and intelligence-gathering activities, etc.; pursuing peaceful conflict resolution based on international law; strengthening relationships with coastal states along sea lanes; and using Artic sea routes and Japan’s base in Djibouti. The Strategy also indicates measures intended to significantly strengthen coastguard capacity and improve relevant systems, and policies such as strengthening international cooperation and collaborating with maritime law enforcement bodies in the US and in countries in south-eastern Asia. All these initiatives will be effective in strengthening the military aspects of maritime security.[2]

Furthermore, among matters relating to energy security presented in the Strategy are stronger relationships with resource-rich countries; supply source diversification and stronger procurement risk evaluation; utilization and development of renewable energy sources and nuclear power; and stronger strategies intended to raise Japan’s energy self-sufficiency rate through collaboration with allied, like-minded countries and international institutions. Measures in the Strategy to improve food security include stable import of and appropriate storage for foodstuff; increased domestic production; ensuring stable food supply by, for example, promoting domestic production of processed goods and production materials for which Japan currently has high foreign dependency; provision of an international food supply environment via collaboration with allied, like-minded countries and international institutions; improvement in domestic food production; and support for vulnerable nations.[3]

As above, the latest National Security Strategy states in concrete terms that Japan will engage in initiatives to strengthen maritime security and coastguard capacity, and to secure energy security and food security. There is, however, little focus on marine transportation, despite the extremely important role of stable transport by sea (the means by which energy resources and food are transported) in strengthening Japan’s economic security and improving the resilience of its supply chains. Thus, this paper examines Japan’s vessel ownership, points to the fact that the nation has a high reliance on non-Japanese vessels in marine transportation, and suggests how Japan’s supply-chain resilience can be improved.

Vessel ownership within Japan’s merchant fleet

Japan is reliant on foreign countries for many goods. For example, according to the Japan Maritime Public Relations Center, the degree of overseas dependence for energy resources is 100% for iron ore, 99.7% for coal, 99.6% for crude oil, and 97.9% for natural gas. For foodstuff, overseas dependence is 100% for animal feed, 94% for soybean, 85% for wheat, 64% for sugar, 62% for fruit, 45% for fish and seafood, and 47% for meat.[4]

Furthermore, energy resources and foodstuff are imported into Japan almost entirely by sea. In 2020, marine transportation accounted for 99.5% of Japan’s import and export trade on a tonnage basis, at just over 856 million tons. Within this, the proportion of Japan’s import and export cargo transported by Japan’s merchant fleet (ocean-going vessels of 2,000 gross tons or above operated by Japanese ocean-going shipping companies) was 48.8% for exports, 62.6% for imports, and 60.1% for imports and exports.[5] In other words, more than half of Japanese exports, and almost 40% of its imports, are transported by foreign commercial vessels.

Japan is known as one of the world’s leading marine transport nations. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) publishes data each year related to global marine transportation. Table 1 shows the number of vessels of 1,000 gross tons or above and shipping tonnage effectively owned by major countries’ shipping companies in 2022.[6]

The shipping tonnage effectively owned by Japanese shipping companies in 2022 is around 236.64 million tons. In terms of global share of tonnage, Greece ranks first with 17.6%, China second with 12.7%, and Japan third with 10.9%. Having said that, the proportion of Japanese-registered vessels, namely vessels under Japanese national flag, in the shipping tonnage effectively owned by Japanese shipping companies is no more than 15.2%. This proportion is of a similar level to that for Greece, Korea, and the UK. However, the proportion of tonnage from domestically registered vessels is 40.7% for China and 64.6% for Hong Kong; compared to this, the proportion of domestically registered vessels for Japan is relatively low.

Furthermore, the number of vessels effectively owned by Japanese shipping companies is 4,007, the third highest in the world, representing a global share of 7.3%. China has the highest number of vessels, at 8,007, with a global share of 14.5%, and Greece ranks second with 4,870 vessels, and an 8.8% share. In terms of the number of vessels as well, the proportion of Japan’s vessels under the national flag is only 23.3%. For Greece, this rate is low at 12.7%, but for China, it is 66.9%, for Hong Kong 47.3%, and for Korea 47.9%. This shows that even though ships are effectively owned by Japanese shipping companies, the proportion of Japanese-registered vessels, in terms of the number of vessels and tonnage, is low compared to major countries and regions in Asia, and reliance on foreign-registered vessels is high.

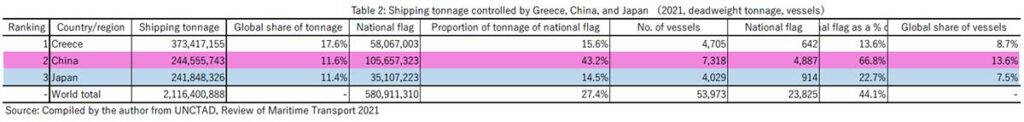

Table 2 shows the shippage tonnage controlled by Greece, China, and Japan, the top three countries in 2021.[7] A comparison of the figures for 2021 and 2022 reveals remarkable growth in the number of vessels and the shipping tonnage owned by Chinese shipping companies. In the past year, China increased its shipping tonnage by approximately 33.3 million (), raising its share of global shipping tonnage from 11.6% to 12.7%. With regard to the number of vessels, more notably, there was an increase of 689 to 8,007, from 7,318 in 2021, a 9.4% year-on-year increase, with a jump in global share from 13.6% to 14.5%. There was also an increase of 470 in the number of vessels under their national flag. Chinese shipping companies are thus steadily increasing the number of vessels and shipping tonnage that they own and increasing their presence in the sector.

Conclusion

Improving Japan’s supply-chain resilience is of high priority if the nation’s economic security is to be strengthened. How a stable supply of energy resources, foodstuff, and other strategic goods can be secured is an issue in need of urgent resolution. Similarly, given that strategic goods are almost entirely transported by sea, marine transportation is a lifeline for Japan’s economic security and supply chains.

Although Japan is one of the world’s leading maritime nations, it has a relatively high dependence on foreign countries in terms of vessel ownership. In recent years, the presence of China in marine transportation has been on the rise. As illustrated by the global distribution stagnation from January 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, it is often impossible to predict the form that crises will take. Moreover, crises can occur suddenly. During ordinary times, Japan should strive to establish a secure environment for marine transportation that will serve to minimize the impact of any crises that may occur.