Economic and technological interdependence with China has been “securitized” over the years as the relationship between the United States and China have become fraught with mistrust and came to be characterized as one of strategic competition. China’s strategy to buy, learn and steal foreign technology, reduce dependence on them, and exploit those technologies for military, industrial and information dominance purposes has been met with US pushback beginning in the years of the Obama administration[2]. Subsequently, US efforts to counter Chinese technology transfer dramatically expanded during the Trump administration. Policymakers now see interdependence as a source of vulnerability rather than benefits. The flow of goods, technology and data between China and the United States have been subjected to various kinds of national regulations, and both governments are ramping up domestic investment in research and development to reduce dependence on the other. Consequently, terms such as selective “tech decoupling” have become common.

The United States and Japan both hold strong security concerns against China while also engaging in significant economic transactions with it, raising risks that the JFIR Proposed Basic Principles have pointed out. Intensifying security competition in a world of globalized networks and a structure of interdependence has made China a particularly challenging actor to manage since it pursues military-civil fusion and leverages economic means to coerce other states for political purposes. In the face of this challenge, the United States and Japan will need to undertake a two-pronged approach: 1) enable deeper R&D cooperation by, among other measures, increasing the connectivity of their respective S&T ecosystems, and 2) coordinate on regulating their interfaces with the Chinese S&T ecosystem.

1. Advancing Deeper R&D Cooperation

The United States and Japan are collaborating on a multitude of initiatives to enhance competitiveness and promote innovation. Recent initiatives include the US-Japan Competitiveness and Resilience (CoRe) Partnership announced in April 2021. According to the fact sheet, initiatives involving 5G Open-RAN and 6G, Global Digital Connectivity Partnership, global ICT standards development, supply chain cooperation, biotech, and quantum information science and technology have been launched.[3] The joint statement of the U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee issued on January 6, 2022 announced that the Ministers “committed to pursue joint investments that accelerate innovation and ensure the Alliance maintains its technological edge in critical and emerging fields, including artificial intelligence, machine learning, directed energy, and quantum computing.”[4] They also agreed to conduct a joint analysis focused on future cooperation in counter-hypersonic technology.

In order to further facilitate R&D collaboration, several efforts could be undertaken. First, the two governments should map the private sector tech innovation ecosystem to illuminate potential cross-border R&D. As Japan is now moving to bolstering public-private partnerships for R&D of certain critical technologies – those related to AI, quantum, space, maritime, among others – as a part of its economic security initiative[5], the two governments should begin by sharing information about their respective R&D public-private partnership programs and identify areas where they can leverage synergy and complementarity. Technology standard-setting efforts should take a multi-partnership approach to include other US allies as well as newly launched cooperative initiatives under the Quad framework.

2. Dealing with China’s Military-Civil Fusion (MCF)

China’s MCF Development Strategy has become a major source of concern for the US government.[6] MCF has raised the question of what not to sell and to whom not to sell in China, and US authorities seem to have found it increasingly difficult to identify military/civil end user and end use as MCF is gradually expanding its scope of involved entities.[7] MCF has been cited by US authorities as a reason to add Chinese companies and academic institutions to the “Entities List” and the “Unverified List,” and declare a US presidential proclamation regarding denial and revocation of visas of Chinese students and researchers having proximate ties to Chinese entities involved in MCF.[8]More importantly, US export regulations have been covering re-export from third countries based on application of rules such as the de minimis rule and the direct product rule. As a result, in the area of export control, US policy in recent years have expanded the scope of military end user and military end use regulations. China has reacted by enacting its own export control act in October 2020.

Thus, the more challenging endeavor would be coordinating on how to control export of dual use emerging technologies in a situation where both the United States and Japan maintain substantial economic exchange with China. While US-China competition over advanced technologies is likely to persist and intensify, a complete technological severance is unlikely. Indeed, most American, European and Japanese companies operating in China appear to maintain their businesses in China even in the midst of intensifying bilateral friction.[9] Academic talent flow between the Chinese and American S&T systems remain[10] (though Chinese students and scholars studying in the United States maybe decreasing in number as a result of Covid, visa restrictions and other measures). As Segal and Kania have pointed out, “[t]he balance between cooperation and competition will vary over time in response to political and geopolitical vicissitudes and will differ across various fields and domains of S&T.”[11]

Given this reality, completely shutting down economic and academic exchange with China based solely on security considerations will likely undermine the American and Japanese bases of economic prosperity and innovation, and thus, policy experts, companies, and academics have called for tailored and calibrated responses adequate for maintaining and bolstering technological and economic competitiveness.[12] This fundamental question of how various national policies should balance security interests derived from strategic considerations and economic interests accruing from free and open commerce and transnational exchange needs to be addressed in various ways depending on the nature of particular challenges.

3. Implications for Japan

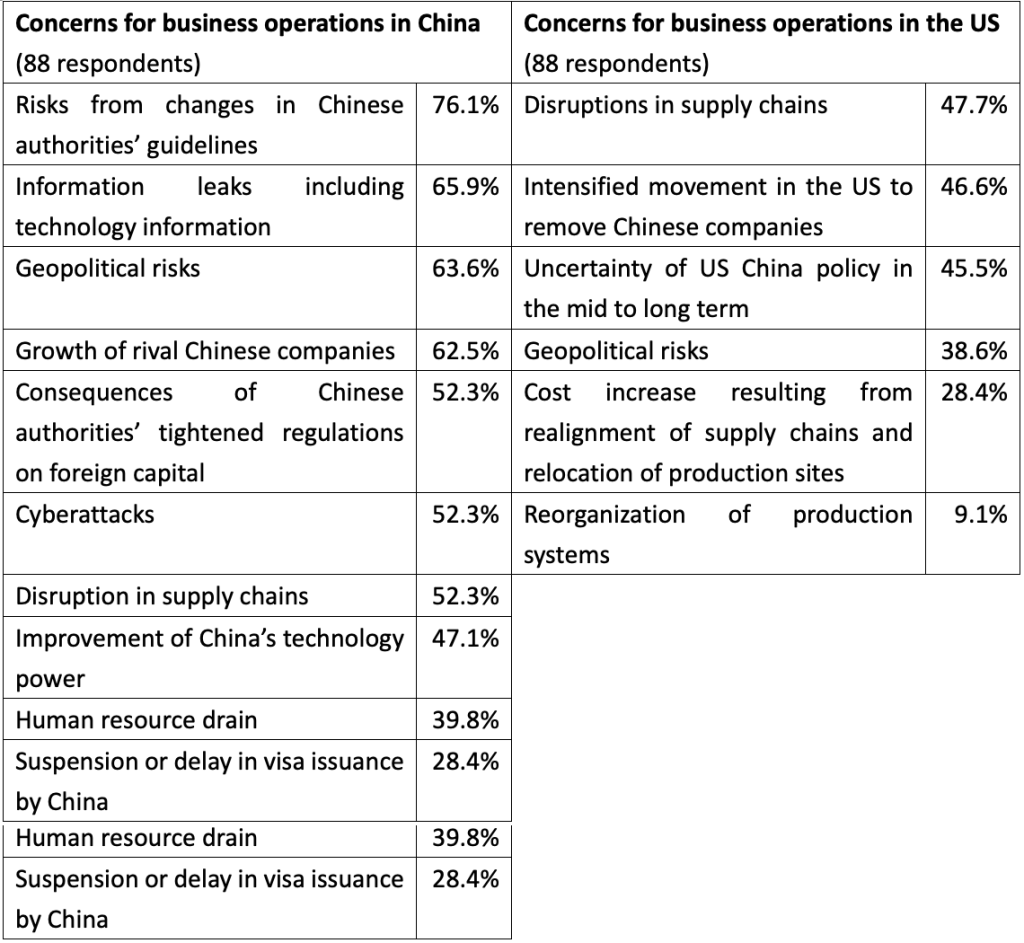

The above trends have generated a sense of uncertainty among the Japanese business community. According to a survey conducted against 100 Japanese firms in November/December 2021 by a Japanese thinktank, 75% of all respondents answered that the biggest issue they face is the “uncertainty of US-China relations” and 60.8% (59 of 97 respondents) replied that their business operations have been affected by the confrontation between China and the United States.[13] 59.5% (44 out of 74 respondents) replied that they have been affected by increased cost resulting from strengthened US regulations (including tariffs), while 33.8% replied that they have been affected by increased cost resulting from strengthened Chinese regulations.[14] 12.5% (12 of 96 respondents) answered that in the past they had faced a situation where they had to choose between the United States and China (no mention of specifics).[15] When asked what concerns they have when operating in China and the United States respectively, they replied as follows:[16]

Source: Asia Pacific Initiative Survey on 100 Japanese Companies, pp, 10, 13.

These concerns appear to have driven 47.4% of the respondents (largest cluster) to desire a clear indication of the direction of Japanese policy to deal with American and Chinese regulations, and 18.6% want the Japanese government to take into account corporate interests when making policy decisions.[17]

Under these circumstances, the main task here is to establish a US-Japan consultation mechanism on joint decisions to apply various export regulations so as to minimize the risk of excessive restriction including those that have extra-territorial implications. The United States would be in a better position if it obtained concurrence from US allies including Japan, and Japan would benefit from such consultation that would allow it explore ways to optimally protect its commercial interests. A future goal would be to form a minilateral regulatory framework for the United States and its technologically advanced allies so that export control is multilateralized effectively through consensual consultative processes.[18] Joint decisions and agreed guidelines should generate predictability for businesses and academia for all the member states.

But in order for Japan to be able to meaningfully engage US authorities, it would need to (i) establish a mechanism to search and survey domestically developed dual-use emerging technologies, and (ii) devise a National Technology Strategy (NTS) to, among other things, identify and define what technologies it wants to protect and achieve some level of self-sufficiency and dependence on trusted partners and what technologies it wants to put into competition in foreign markets as leading (indispensable) technologies. The NTS should also contain human talent acquisition strategy as China is expected to double down on its talent acquisition efforts on a global scale to counter US policies.[19] Without a backbone strategy, Japan will be merely reacting to Chinese and American regulations and policies on an ad hoc basis. Thus, the true challenge for Japan is to devise the NTS based on security and industrial considerations to effectively manage technological competition with China over the long haul.[20]