1. Introduction

Maritime shipping is a commercial activity operated by private enterprises. In the process of pursuing and realizing the national interest, nationality presents a legal issue when the government deals with private individuals and companies for employment reasons. The nationality of the vessel charter, of the ship’s crew, and of the shipping company as a corporate entity are the basic issues in shipping. Logically, it is possible for a sole proprietor to run a shipping business, but as this is not realistic, this paper assumes that such companies will be organized as corporate entities.

2. Shipping companies and their corporate nationality

(1) Shipping companies

Shipping companies, as carriers, use ships (by conducting voyages) to provide the service of marine transportation to shippers (owners) and earn profits by collecting freight and charter charges for the fulfillment of this service. This practice (called “operation” or “commercial operation”) is the basis of the business of shipping.

Shipping companies, as carriers, may own their own ships or lease (charter) them from other companies. Therefore, this paper will henceforth separate the functions of shipping companies into those of shipowners (owners) and charterers (lessees, but often referred to as “operators” in business practice). [1]

(2) Shipping company nationality

The nationality of a shipping company as a legal entity is determined by the country pursuant to whose law of companies a given firm is incorporated.

For a shipping company to own a Japan-flagged ship (“Japanese ship”), the company must be incorporated under Japan’s Companies Act, and nationality requirements for officers (representative directors and executive officers) are specified in Article 1(3) and (4) of Japan’s Ship Act (Act No. 46 of 1899).

3. Chartered Foreign Vessels

It is quite common for shipping companies to register their ships in a country other than the country governing the incorporation of the company. Such a ship is referred to as a ship of convenience. As of January 1, 2020, 71.6% of the world’s merchant shipping capacity (deadweight tonnage) was registered abroad [2]

Although there has long been criticism of the harmful effects of Flag of convenience ships, these harmful effects have now been overcome and there is no longer any basis for criticism [3]

To use a flag of convenience vessel, a shipping company, as the parent company, establishes a foreign subsidiary or affiliate company in accordance with the corporate laws of the country where the vessel is to be registered; that company owns the vessel, which is then registered by that country. The parent company then charters such ships from the foreign subsidiary/foreign affiliate.

4. Japanese Merchant Fleet

(1) Japanese Merchant Fleet

The term “Japanese Merchant Fleet” is used in Japanese maritime administration. This fleet consists of Japan-flagged vessels, which are owned by shipping companies with Japanese nationality, as well as foreign-flagged vessels that are chartered by Japanese shipping companies from foreign shipowners. All these vessels are owned, operated, and managed by Japanese shipping companies (operators), which act as underwriters for cargo transport and are engaged in earning freight and charter rates from shippers for cargo transportation.

(2) Foreign vessels in the Japanese Merchant Fleet

As of 2020, there will be 2,411 vessels in the Japanese Merchant Fleet. Japan-flagged vessels (“Japanese vessels” as defined in Article 1 of the Ship Law) account for 273 vessels (11.3%), while foreign vessels account for 2,138 vessels (88.7%). Of the chartered foreign vessels, 538 vessels (22.3%) are chartered (“chartered-in”) exclusively by foreign shipping companies (“simple foreign chartered ships”) and 160 vessels (66.4%) are Japan-flagged ships of convenience (referred to as “Shikumi-sen” in the industry jargon) [4]

(3) Existence of “Japanese shipping company”-affiliated vessels not included among the Japanese Merchant Fleet

There are vessels owned by Japanese shipping companies, either by the firms themselves or by their foreign subsidiaries/foreign affiliates, that are not included in the Japanese Merchant Fleet under the law. The basic reason for this arrangement is that the entity that manages the operation is a company located in a foreign country that is not subject to Japanese sovereignty (not only shipping companies but also oil and gas companies, grain trading companies, etc.).

Specifically, these include ships used for foreign resource transportation projects such as liquefied natural gas, ships “chartered out” to purely foreign shipping companies, and ships operated and managed by overseas subsidiaries of Japanese shipping companies. It was estimated that 247 (33.0%) of the 748 vessels operated by Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha (NYK Line) in 2020 would not be included in the Japanese Merchant Fleet.

It is clear that Japanese maritime shipping companies will be expanding their response to overseas markets to an ever-greater extent. Thus, the “fleet of Japanese shipping companies that are not part of the Japanese Merchant Fleet”—that is, the number of ships associated with Japanese shipping companies that are not subject to Japanese sovereignty—will continue to rise in the future. Additionally, this means that the source of profits for Japanese shipping companies will shift from their parent companies to their overseas consolidated subsidiaries and affiliates.

(4) Quasi-Japanese vessels

Of the structured vessels, the number of quasi-Japanese vessels, as defined by Article 39-5 of the Marine Transportation Act (Act 187 of 1949), is very small, as revealed during a Diet hearing, with a figure of 41 vessels as of the end of June 2015 [5]

A quasi-Japanese vessel is a vessel other than a Japanese vessel (in essence, a structured vessel) owned by a subsidiary of an ocean-going shipping company and certified by the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT).

Although MLIT certification is subject to other conditions, once the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism issues a voyage order under Article 26(1) of the Marine Transportation Act, it is important that the foreign shipping company enter into a contract with the foreign subsidiary to receive the transfer or lease of the ship (this is a charter contract in the form of bareboat; Article 39-5, Item 2).

Foreign subsidiaries owning structured ships are usually wholly owned and controlled by the parent company, and as all the officers are typically all employees of the parent company, the conclusion of a contract for the transfer or bare chartering of a ship is itself a foregone conclusion. The question is, is it possible to transfer or lease the ship and change the ship’s registration as soon as the order to sail is issued?

It can be concluded that it is generally difficult to do so.

This is because even if a foreign-flagged ship is said to have been built with equipment that conforms to the domestic laws of the country where the foreign government implements the SOLAS Convention, the equipment installed may not necessarily be type-approved as stipulated in Article 6-4 of the Ship Safety Act (Act No. 11 of 1933), which implements the SOLAS Convention in Japan, and separately, large-scale construction and cost such as obtaining approval through a separate inspection or replacing the equipment with approved equipment will occur.

Therefore, the shipyard should be informed from the outset of the plans to convert the vessel to Japanese charter in the future, and it is practical to apply to the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism for certification of the foreign-flagged vessel as a quasi-Japanese ship in light of the practices of shipping companies.

However, unless it is possible to predict a strong cargo market, private companies will not immediately decide to build new ships (even if they receive tax incentives) even if the government policy is to increase the number of Japanese and quasi-Japanese vessels.

5. Crew nationalities

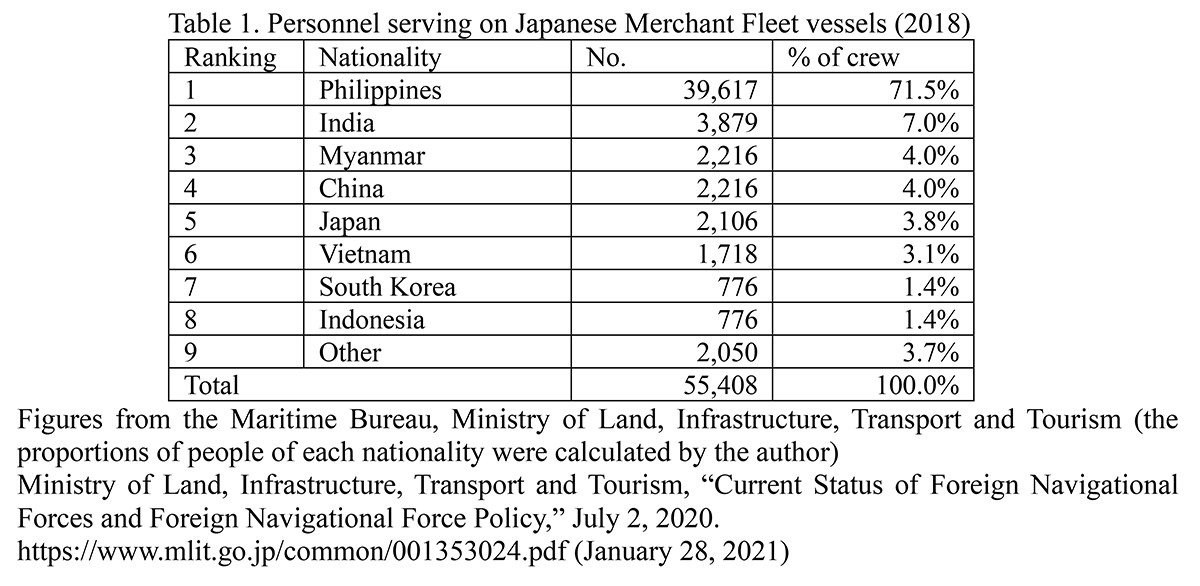

The chart below shows the nationalities of the crews assigned to the Japanese Merchant Fleet. In terms of human resources, 96.2% of Japan’s shipping industry relies on foreigners. In particular, Filipinos account for 71.5% of the total.

Crew members can be roughly divided into staff (professionals) and crew (simple labor). Since the late 1960s, Japanese shipping companies have been replacing crew members engaged in simple labor onboard ships with foreign nationals in consideration of labor wages, and since the early 1990s, these entities have been gradually replacing corporate staff with foreign nationals as well, starting with lower-ranking staff. Foreign crew members were appointed as lower-level staff members because of the lower wages and to positions such as captain or chief engineer, because by around 2000, there were fewer Japanese young people graduating from merchant marine colleges and technical colleges who wanted to become crew members.

Since the early 1990s, Japanese shipping companies have been operating their own crew training schools in the Philippines at the vocational school level or higher in cooperation with their Philippine partners. NYK Line and Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Inc. have private merchant marine colleges that are accredited by the Philippine Higher Education Authority to grant bachelor’s degrees [6]

The issue of whether to allow foreign crews on board a Japan-flagged ship is not a matter of law but merely a matter of labor-management agreement. Therefore, it is not uncommon nowadays to find ships of Japanese charter in which “(all) crew members are foreigners.” Today, approximately one-third of the crews employed by major Japanese shipping companies are graduates of Japanese merchant marine universities and merchant marine technical colleges, their own crew training schools in the Philippines, and general universities (so-called in-house training).

6. Tonnage Tax System

In maritime shipping, it is common for shipping countries to have a tonnage tax system pertaining to tonnage handled. Such systems of taxation impose taxes not on the amount of corporate income, but on the “external form” of a shipping company, i.e., the size of its ship operations. This is because the shipping market fluctuates greatly. Under the external taxation system, companies would pay tax according to the size of their fleet, but the amount of tax paid would be stable regardless of market fluctuations; as the taxation is not proportional to corporate income when the market is booming, this system is intended to promote capital accumulation at those times to prepare for when the market slows. However, since this is a size-based Business Tax, tax payment is required even if corporate income is negative.

The tonnage tax system was introduced in Japan through Article 38 of the Marine Transportation Law. However, in Japan, there are differences from other countries [7]. First, the fleet of a shipping company subject to the tonnage tax is limited to Japanese ships and semi-Japanese ships and does not include all ships in operation (Article 59-2 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation (Act No. 26 of 1957)).

Second, the Japanese government will require shipping companies to increase the number of Japan-flagged vessels and employment of Japanese crews in exchange for the application of the tonnage tax system and will monitor the achievement of these goals (Article 35, Paragraph 3, Item 5/38). This does not mean the unconditional application of the standard tonnage taxation system, as in other countries [7]. From the government’s perspective, this is meant to increase the number of Japan-flagged ships and the number of Japanese crewmen, to which end they will give tax benefits to the shipping companies. The fact that young Japanese do not want to become ship crewmen is shown in Section 5 above. The fact that the construction of ships depends on the outlook of the cargo market has been discussed previously (Section 4.4).

By contrast, shipping companies that do not want to be obligated to increase the employment of Japanese crews and increase the number of Japan-flagged vessels will not seek to apply the standard tonnage tax system. In fact, there are only six shipping companies that are subject to the tonnage standard taxation system [8]

This is one proof that Japanese shipping companies are at a disadvantage in terms of taxation compared to companies in other shipping countries, even though Japan is a shipping powerhouse with the second largest merchant fleet in the world [9] Furthermore, with the exception of tax havens (e.g., the Japanese government’s response to the tax exemption on foreign income from the country of registry for owning ships of convenience), the corporate taxation of companies is in essence paid by the Japanese shipping company (parent company) alone. However, it was mentioned previously that the revenue of Japanese shipping companies will gradually increase from their consolidated subsidiaries and affiliates (Section 4.3).

Therefore, it is not surprising that considering only purely economic factors, the management of the shipping companies may wonder whether they should continue to choose Japan as their corporate nationality.

7. Japanese shipping companies in the near future: Conclusions

Some Japanese shipping companies (operators) have established their own shipping companies in Singapore under the Singapore Companies Act. This was the case with Ocean Network Express Pte. Ltd., a new company that integrates the container ship divisions of Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha, Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, and Kawasaki Kisen Co., Ltd. (hereinafter, the “Big 3 Japanese shipping companies”). The company is wholly owned by Ocean Network Express Holdings Corporation (henceforth referred to as the “Holding Company”), which was established in Tokyo, and Big 3 Japanese shipping companies are shareholders of the Holding Company.

In other words, Big 3 Japanese shipping companies have been reduced to non-functional capitalists who expect only profit dividends from the containership business, except for the regular chartering of containerships to overseas operators.

There are already business units, such as petroleum product and chemical tanker transport firms, whose sales and operations have been completely transferred to overseas subsidiaries. The time will come when the reason Japanese shipping companies are called “Japanese-affiliated” will be explained only by the memory of the historical origin of the companies.