1. The Need to Reconsider Geopolitics and the Concept of the Sphere of Influence

The term geopolitics was largely avoided for a long time as it evoked Nazis, but has returned and become popular since the last years of the Cold War. It is also an important concept in our research group. It cannot be denied, however, that quite a few researchers still feel doubt over this term. In journalistic studies which are often jeered as “general geopolitics”, while classical concepts such as land power and sea power, heartland and rimland, and lebensraum and sphere of influence are used as catchwords, in concrete terms simple power politics and struggles over resources are often discussed without deeply analyzing geographic issues.

On the other hand, “critical geopolitics” became dominant in political geography, and there has been more research which deconstructs classical geopolitics as well as state centralism and environmental determinism therein and analyzes politicized geographic images, especially those biased to Western-centrism.[1] While critical geopolitics is beneficial for a critical understanding of international politics, it does not directly lead to useful proposals for policy-making. This paper reconsiders the concept of the sphere of influence, referring to theories on regionalism and critical geopolitical epistemology, and explores how geographic factors in international politics and the combination of geography and history, culture, economy, and military should be positioned in policy-oriented research.

The fact that geography is not seriously analyzed in “general geopolitics” seems to be linked to the idea that international politics has become less constrained by geography due to the progress of globalization and the development of transportation, information and communications technology, and military technology. However, the importance of geography is evident by looking at the recent international political situation. Needless to say, territorial problems occur between geographically adjacent countries, and as shown in the Nagorno-Karabakh war, which drastically intensified in 2020, and in various territorial issues of Japan and China, a territorial problem in a place without major economic importance can symbolically be a serious focal point. Relations between neighboring countries, such as the Japan-China and Japan-Korea relations, have a lot of ups and downs, and even the EU, which seemingly deepened its regional consolidation, experienced Brexit. Still, international relations that share a geographic framework, such as East Asia and Western Europe, are very important, regardless of the relationship being cooperative or hostile. The COVID-19 issue highlighted the importance of border control and cooperation between neighboring countries.

Globalization and the development of technology have not changed the geographic images that constitute the base of diplomatic policies of various countries. China, Russia, and Turkey continue to envisage the largest territory of their predecessor empires as the sphere of influence that the countries should have. The images of friendly nations, enemy nations, and dangerous nations, including the U.S.’s hostility toward Iran and distrust in Russia, has been continuing since the second half of the 20th century. On the other hand, there are countries that seek to enhance their presence by creating or manipulating geographical images, such as China, which declared the Belt and Road Initiative, Russia, which advocates Eurasianism in a broad sense, and Japan, which created a new diplomatically geographic image, Indo-Pacific.

However, none of the existing geographic concepts or new frameworks automatically become the sphere of influence of a country. In the present world, all countries have complex relations with various countries, and a monopolistic or exclusive sphere of influence is unlikely to be established. Below, the author would like to discuss the difficulty of forming a sphere of influence, and the conditions for establishing a scope in which the influence of a country is relatively strong, on the examples of regionalism and regional cooperation led by Russia and China.

2. The Eurasian Economic Union and the Belt and Road Initiative in the Context of New Regionalism

Regional cooperation organizations, particularly the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), constituted by five post-Soviet states, and the Belt and Road Initiative led by China are often cited as attempts to form a sphere of influence in today’s world. However, Russia and China stress that the organization and project have an open nature. Given that they actually have various countries as members or partners, the open nature is not a lie.

This needs to be understood from the tide of “new regionalism”, which was a global presence in the 1990s and 2000s, when Russia and China began to envision the way of regional cooperation. The term “new regionalism” has a variety of meanings, but it generally means that a regional-cooperation organization or framework is formed by diverse members in the context of a multipolar world and globalization, having an open nature in an interdependent global economy. This is therefore compatible with the concept of “open regionalism”, which has often been used regarding regional cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region since the latter half of the Cold War. As Mie Oba points out, the meaning of “open regionalism” is contradictory because regionalism essentially contains a closed nature that separates the inside and the outside, and relations with outside regions consist of both competition and reconciliation.[2]

Russia-led regional cooperation primarily aims at strengthening relations among the countries of the former Soviet Union, and it has a stronger commonness based on historical foundations and spatial limitation compared to what is generally assumed as new regionalism. However, countries in the western part of the former Soviet Union have been under the influence of the attractive force of European integration, and the strengthening of relations with Russia has not necessarily been the best option. Russia, which dislikes the expansion of the EU and NATO, stirred things up for Georgia and Ukraine, which are pro-U.S. and -Europe, through regional conflicts and military intervention, but these actions, while putting both countries in distress, made it difficult to restore their relations with Russia. Russia-led regional cooperation clearly has an intention to reduce the influence of the outside world, particularly from the United States and Europe, but cooperation is limited to countries that have been pro-Russian from the outset, with limited influence from Europe and the United States.

It is hard to say that the EAEU, which is composed of pro-Russian countries, can be freely used by Russia for its benefit under its strong leadership. The establishment of relations among the countries of the former Soviet Union after its dissolution is based on the principle of equality, although there are exceptions. When Russia engages with other countries for regional integration and cooperation, equality is essential as a means to persuade them. In the decision-making body of the Eurasian Economic Union, each country has an equal voting right, regardless of the country’s economic size.

The period where the EAEU was built was when the EU was recognized as a successful example of regional integration, and the design of the system, where an organization that equally represents the benefits of member states (e.g., Supreme Eurasian Economic Council) and a superstate organization that prioritizes the interests of the whole (e.g., Eurasian Economic Commission) work together, is heavily influenced by the EU’s European Council and European Commission. Because the countries of the former Soviet Union, including Russia, have a strong commitment to national sovereignty, however, the scope of delegating part of sovereignty to the superstate body in the EAEU is much smaller than that in the EU, and decisions made with the consensus of equal member states is more pronounced.

Importance of equality and consensus among the member states is directly linked to the fact that Russia’s intentions are not easily realized in the EAEU and the deepening of integration is restricted. Russia’s sanctions on Ukraine and reverse sanctions on Europe and the United States did not become an EAEU-wide policy, and caused many problems because sanctioned goods entered Russia via other member states. Kazakhstan has been strongly opposed to the introduction of common currencies and various measures for non-economic integration, which is often suggested by Russian leaders and officials. At the same time, in the spirit of new regionalism, the EAEU is gradually increasing its observer states and states with which free trade agreements have been concluded, which leads to lower barriers between member and non-member states. More importantly, when a member state establishes a relationship with a country/organization outside the area, it does not have to take into account the EAEU, except for things related to duties. Many member states are strengthening their relations with the EU and other Asian countries. As explained above, it is difficult to say that the EAEU is promoting Russia’s strong sphere of influence.

China strengthened its relations with Russia and Central Asian countries in the 1990s to foster trust in the border region, and led the establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in 2001. The SCO has advocated the principle of openness in its founding declaration in line with the new regionalism. While it was sometimes reputed as an anti-U.S. organization, it has essentially avoided conflict with outside countries. The SCO is also an organization that reflects China’s diplomatic view, such as the “new security concept”, but it is not possible for China to demonstrate strong leadership because another major country, Russia is its member. Because the SCO places even greater emphasis on national sovereignty and noninterference in internal affairs than the EAEU, it is suitable for demonstrating friendship among member states at summit meetings, but lacks the ability to act as a supernational organization.

The Belt and Road Initiative was proposed in 2013, when the SCO’s activities had become routine. It can be positioned as part of China’s great-power diplomacy, including the “community with a shared future for mankind” concept advocated in 2012 and the “major-country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics” concept in 2014. It originally gave a strong impression of regionalism and even the concept of the sphere of influence, covering regions on land and sea routes that connect China and Europe. But soon, the initiative started to incorporate regions that were not located between China and Europe, such as inland Africa and Latin America, and it became international cooperation that used regional rhetoric but actually did not form a region. The initiative is also quite different from regional cooperation organizations such as the EAEU and SCO in that it is a compilation of bilateral relations that allows flexible absorption of diverse countries in various forms and degrees by not identifying membership and by not promoting strict institutionalization. These characteristics show that China’s ambition to become a global power is spreading around the world by breaking the mold of regionalism, but they also show that it is difficult for China, which often encounters rejections in various ways, to maintain its influence in particular regions.

As explained above, both Russia and China have a preference for building a sphere of influence while strengthening their assertiveness as a major country, but they need to take into account the principle of equality among sovereign countries and new regionalism when they lead regional cooperation, and there are few countries that do constantly cooperate with them. It cannot be said that they have succeeded in forming a secure sphere of influence. On the premise that a monopolistic and exclusive sphere of influence cannot be established in the current world in the first place, however, observation of relative influence of each country will reveal a slightly different aspect. The next chapter will discuss that.

3. National Power + Involvement + Ability to Create Empathy = Influence

While Russia does not have an exclusive sphere of influence, it still has a strong presence in the post-Soviet space. Although the development of the Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020 was not necessarily what Russia wanted, Russia achieved a ceasefire by mediating Azerbaijan and Armenia in the final phase, demonstrating that it is Russia, not Europe, the U.S., or Turkey, that can arbitrate conflict in the post-Soviet space (except for conflict where Russia is a concerned party). In Central Asian countries during the COVID-19 crisis, while doctors from China mainly made inspections and gave general advice, doctors from Russia often stayed there for about a month to discuss treatment policies and conduct actual treatment with local doctors, who often voluntarily referred to Russian treatment themselves. It was clear that Russia’s cooperation was more fine-tuned.[3] The countries of the former Soviet Union have a long history of making up one country and share a common Russian language, various systems, customs, and senses. Russia continues to engage with these countries in various forms of bilateral involvement outside the framework of regional cooperation organizations, although the economic scale of the involvement is limited. Relations with pro-Western post-Soviet countries often become extremely poor as a result of that Russia’s negative involvement, including military intervention, but Russia has a stable foundation in relations with other countries of the former Soviet Union.

In addition to the post-Soviet space, Russia has had various channels of exchange with countries in the Middle East since the Soviet era, particularly supporting Syria and Iran’s opposition to Europe and the United States while maintaining good relations with the anti-Iran and pro-U.S. Gulf countries and Israel. While the Russia threat theory is strong particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, there is some sense of familiarity with the Putin administration among nationalist and authoritarian forces around the world, including Japan and the West. There are many Russian culture fans around the world, too, although this does not necessarily lead to political support. While Russia’s overall reputation in the world is never good, it can be said that Russia has something to be called a “sphere of involvement” or “sphere of empathy” and maintains its decent influence, thanks to historical connection and deep involvement with several regions, and empathy that spreads through people in some regions and of some categories, in addition to its national power derived from its military power and natural resources.

China is leveraging its economy and is actively engaged in many countries around the world through the Belt and Road Initiative and other projects, but it is difficult to say that China is expanding familiarity and sympathy throughout the world that match its efforts. In Central Asia, where neighboring China has made significant progress in trade, investment, and aid since the 2000s, the governments are enthusiastic about exchanges with China, but the general population is not. Particularly in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, some of the people have shown strong opposition to China, which is a limiting factor for government-level projects.[4] In more distant regions, relations with China may become more unstable;Sri Lanka moved away from and then re-approached China due to the changes of the government, and European countries had high hope for cooperation with China at the early phase of the Belt and Road Initiative, but have become much more vigilant against China’s hegemonism.

Although China has not been able to expand the areas in which it stably exercises its influence and maintains close relations, China’s active involvement in all parts of the world prevents criticisms toward China over human rights issues and problems related to Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan from spreading to countries other than the United States, Europe, and their allies. In October 2020, 39 countries represented by Germany, including Western countries and Japan presented a statement of significant concerns over the situations in Xinjiang and Hong Kong to the United Nations. As opposed to this, 45 countries represented by Cuba and 54 countries represented by Pakistan (including China itself) presented statements defending China over Xinjiang and Hong Kong, respectively. Countries in defense of China spread across various regions, but when looking at the neighboring regions of China, there were no countries in Central Asia that signed these statements, and few in Southeast Asia. In 2019, 37 countries defended China over Xinjiang, and while the number of supporting countries increased in 2020, 10 countries (such as Tajikistan and Turkmenistan) that supported China in 2019 ceased their support in 2020.[5] Even though pro-China countries are on an increasing trend, they are not stable at all. In general, China is using its national strength based on the rapidly growing economy to engage with various countries around the world. However, this has caused feelings of resentment towards China to spread in the United States, Europe, and Japan, and it cannot be said that China has steadily expanded sympathy for its cause in other countries. While China’s influence is generally increasing, it is unstable and geographically dispersed.

Let’s take a quick look at the influence of the United States. As a superpower for many years and one of the core countries of the Western civilization, the United States has had deep connections with Western European and English-speaking countries, and established alliances with several Asian countries. Compared to other major countries, the United States has maintained a relatively stable sphere of influence. While the United States has engaged in many regions of the world and has strong soft power to create empathy, the country has also been provoking backlash due to its self-righteous actions and cannot easily fill the psychological distance between it and countries other than its allies. In recent years, the United States has become more inward-oriented and its involvement in other countries has become weakened and unstable. This has weakened the source of the influence of the United States. The Trump administration, in particular, severely damaged its relations with Western European countries by its whimsical politics and negligence of allies.[6] On the other hand, the opposition to U.S.-centrism and its interference in internal affairs of other countries has not noticeably weakened, and, while the United States and Japan saw the prevalence of China’s conspiracy theory over the COVID-19 crisis, U.S. conspiracy theories got about in Russia, Central Asia, the Middle East, and China. The existence of opposition to the United States allows China and Russia to expand support for them in a number of regions around the world.[7]

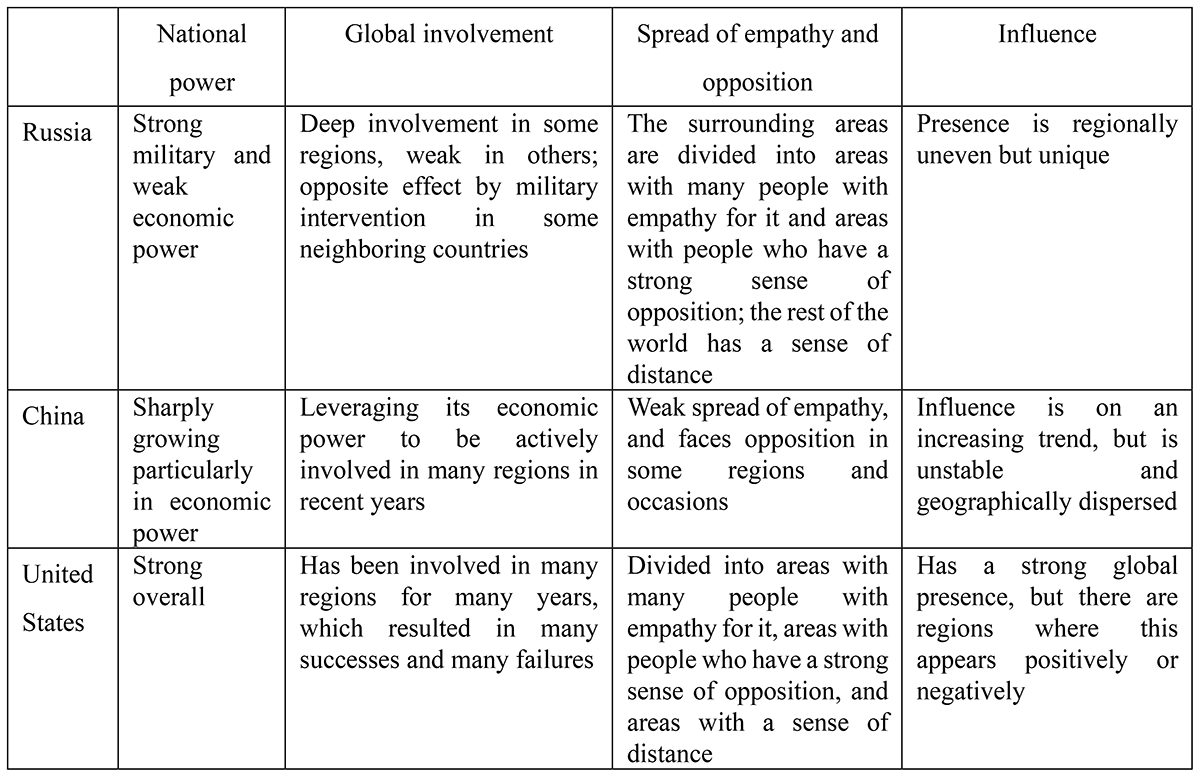

Table: Relationship between the power, involvement,

empathy and influence of Russia, China, and the United States

In summary, the formula “national power + involvement + ability to create empathy = influence” is established. However, it should be noted that negative involvement can produce reverse effects and reduce influence. Comparing Russia, China, and the United States, Russia and China share the same feature in that they have limited areas they are good at, China and the United States share the same point in that they are involved in all parts of the world but said involvement is not necessarily stable (whereas Russia is deeply involved in particular regions), and Russia and the United States are the same in that they have geographically defined areas of influence (China’s influence is unstable and geographically dispersed). What creates these common features and differences is more than just natural geographic conditions such as sea and land, but rather a combination of the geographic spread of the sphere of involvement that the three countries have formed, the quality of the involvement, and images other countries have on the three. The background is the difference in power as major countries and the stages of prospering and declining: the United States has many allies and enemies as a long-standing superpower, Russia has been shrunk from a superpower to a regional power, and China is in a hurry to become a superpower from an ancient empire via marginalization in modern history. The relationship between international politics and geography cannot be narrated without history.

4. Lessons for Japan

Forming a sphere of influence is not Japan’s priority, and is not realistic for it. An idea emerging in recent years is to strengthen cooperation with major countries including the US, India, Australia, and other developed countries of the Five Eyes, and some Southeast Asian countries that can share a sense of the Chinese threat. Of course, it is necessary to strengthen security preparations against China. However, given that the policies and attitudes toward China in candidate countries for cooperation can change depending on factors such as the change of administration, and that the future of China (e.g., how long will its economic growth continue?; how long will it continue to have an aggressive and confrontational diplomatic stance?) is uncertain, it is dangerous to consider a long-term diplomatic strategy solely based on opposition to China’s threat. If Japan focuses only on relations with major powers, it’s presence may be undermined. Japan’s long-term goal should be to enlarge its influence as much as possible and increase as many countries that are influenced by it and have empathy for it as possible, regardless of the attitudes of other major countries and the rise and fall of China’s influence.

For a long time, Japan has been striving to establish friendly relations with as many countries as possible to overcome its negative legacy as a defeated country, and restore its position in the international community, particularly in the United Nations. It was important to engage constructively with developing countries in Asia and other regions through aid and economic cooperation. Its high technology standards and unique culture have also given a positive image to people in most countries. Although it is handicapped in the areas of military, international political power, and language, it has widened international involvement, expanded empathy, and formed a geographical area in which it can have some influence, especially in Asia. In recent years, however, as epitomized by the reduction of ODA, the involvement in developing countries has been sluggish or has decreased, and the economic and technological superiority has started to become questionable.

In such a situation, Japan will not be able to maintain empathy and influence unless it exerts considerable efforts and resources outward to constructively engage in many countries, overcoming its inward-oriented momentum. Involvement in developing countries will become more difficult in ways that utilize the overwhelming difference in economic and technological power as it used to be. However, the author believes that Japan can find a method of attentive involvement that differs from superpowers like the United States and China by utilizing its experience of diplomacy with Asian and developing countries.

It should be noted that even though such involvement may potentially lead to competition with China, just placing competition in the foreground will not gain empathy and potentially cause an opposite effect. The idea that the world order centered on the United States is the best and other countries such as China threatening it are absolutely evil is not widely shared by countries that are not U.S. allies. Although it is important to share the perception of threat with allies and semi-allies, preaching other countries about the threat of China could lead to distrust in Japan’s diplomatic attitude and tempt them to use Japan’s competition with China as a resource for negotiation to draw benefits from Japan. Rather than downplaying other countries, enhancing its image by maintaining national power (especially democratic and open politics and cultural power) and constructive foreign involvement to occupy a large place in the mental geography of various countries’ people, could consequently enhance Japan’s ability to compete with other countries.