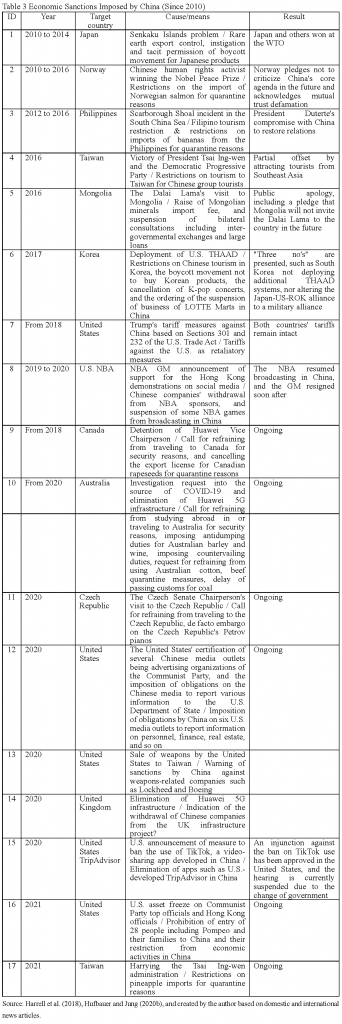

In recent years, China has frequently imposed economic sanctions as a means to maintain and expand its own strategic interests. For example, since 2010, even just in those confirmed in prior studies and various press reports, there are seventeen cases in total involving economic sanctions that were imposed or warned of regarding Japan, Norway, the Philippines, Taiwan, Mongolia, South Korea, USA, Canada, Australia, and the Czech Republic with a wide range of means (see Table 3 at the sentence end). This paper uses these cases to organize the reasons, measures, impacts, and effectiveness of the economic sanctions imposed by China, and to derive the geoeconomic implications.

The term “economic sanctions” is defined in a variety of ways, but here, it is used to mean “a government-led deliberate withdrawal or threat of economic relations, aiming for maintaining and expanding the strategic interests of a country itself [1].” However, it does not cover cases where China participated in multilateral economic sanctions based on the resolutions by the UN Security Council, such as sanctions against North Korea, rather it only covers those that China has independently imposed. It also does not cover cases where military threat is used or the use of measures such as detention of foreign nationals in China (so-called hostage diplomacy), but is limited to sanctions through economic means. In addition, this paper does not cover, for considerations, attempts to guide other countries to act in accordance with China’s strategic interests in the short term or long term by promising or providing generous economic support (the “carrot” of the carrot and the stick policy).

1. Reasons for the Imposition of Economic Sanctions

Why has China imposed economic sanctions? Looking at past cases, China has imposed economic sanctions (1) when China’s national interests, including so-called “core interests,” such as matters concerning territories, security, Taiwan, Tibet, and democratization problems, etc., have been infringed upon or denied by foreign countries, or (2) when foreign countries have been first to impose economic sanctions on China. The following is a list of the reasons why China has imposed economic sanctions using the cases listed in Table 3 in an organized way.

(1) Infringement or denial of core interests, etc.

Territorial issues

Cases where China has imposed economic sanctions on the grounds of territorial problems are:

– Measures to restrict exports of rare earths to Japan on the pretense of environmental protection and resource conservation after a collision incident between a patrol vessel of the Japan Coast Guard and a Chinese fishing boat that occurred in the vicinity of the Senkaku Islands on September 7, 2010 [2]((Case 1 in Table 3), and

– Measures taken against the Philippines to restrict travel after the Scarborough Shoal incident in the South China Sea in April 2012 and the stricter quarantine measures for Philippine bananas [3]((Case 3).

Security reasons

#The confirm<ed economic sanctions imposed on the grounds of security reasons include the following in response to South Korea deploying Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system missiles in March 2017:

– Measures to restrict the travel of Chinese tourists to South Korea [4];

– Boycott movements for Korean products;

– Calling off of K-pop musicians’ concerts in China;

They also include the following as sanctions against the LOTTE Group that provided a site for the deployment of THAAD missiles in South Korea:

– Business suspension imposed on LOTTE Marts in China on the grounds of the fire defense law. [5]

Taiwan and Tibetan problems

Cases related to the Taiwan problem are:

– Measures to restrict the travel of Chinese tourist groups to Taiwan, which were implemented after the Democratic Progressive Party ‘s Tsai Ing-wen took office in May 2016 [6] (Case 4);

– An embargo on the Czech Republic’s Petrov pianos, which was invoked after an official visit to Taiwan by Czech Republic delegates including Senate President Milos Vystrcil in August 2020 [7](Case 11)

– Warning of the sanction invocation against Lockheed Martin and other U.S companies in October 2020 in response to the U.S. Department of State approving weapons sales to Taiwan (Case 13); and

– Measures to ban imports of Taiwanese pineapples for quarantine reasons, which was implemented in March 2021 [8](Case 17).

Sanctions regarding the Tibet problem include:

– Raise of import fees for Mongolian minerals (e.g. copper concentrates) in protest against the Dalai Lama’s visit to Mongolia in November 2016; and

– Announcement of a suspension of the assistance program for Mongolia [9](Case 5).

Democratization problems

Sanctions related to China’s democratization problems include:

– Measures to restrict the import of Norwegian salmon for quarantine reasons, which were taken after the Nobel Peace Prize was won by democratic activist Liu Xiaobo in October 2010 [10](Case 2); and

– The withdrawal of NBA sponsors by Chinese companies after the General Manager (GM) of the National Basketball Association (NBA) Houston Rockets expressed his support for anti-government and democratization demonstrations in Hong Kong on Twitter, and a partial broadcasting suspension of NBA matches in China in October 2019 [11](Case 8).

(2) Countermeasures against economic sanctions against China#

Since 2018, the U.S. Trump administration has imposed:

– Additional tariffs under Section 301 of the Trade Act on China’s forced transfer of technology and infringement of intellectual property rights; and

– Additional tariffs under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act for national security reasons against the increase in imports of some items from China and other countries several times. As countermeasures to the United States’ series of unilateral measures, China imposed a wide range of tariffs on imports from the United States [12](Case 7).

As other countermeasures against the United States, China imposed an obligation to report on financial status and real estate to China on four U.S. media companies (such as the AP) operating in China in July 2021. This was in response to the U.S. government designating Chinese media, including the People’s Daily, as being the “Chinese government’s advertising organizations,” and imposing an obligation on Chinese media to provide information about employees and held real estate to the U.S. Department of State since February 2021 [13] (Case 12). In September 2020, the United States announced measures to ban the download and update of TikTok and WeChat developed in China in the U.S. In December of that year, China removed multiple apps, including the U.S.-developed TripAdvisor app, from app stores in China. Some point out that this is considered as China’s countermeasure against the United States [14] (Case 15). Finally, in January 2021, when the U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo (at that time) announced a freeze on the assets of top officials from the Chinese Communist Party and others [15] in response to the democratic-wing oppression problem in Hong Kong. One week later, China imposed measures against 28 Americans, including Mr. Pompeo, banning entry into China and banning economic activities in China [16](Case 16).

As a countermeasure against countries other than the United States, in December 2018, when Canadian authorities arrested Chinese Vice Chairperson of Huawei, Meng Wanzhou under a request from the U.S. government, China also arrested two Canadians for spying in retaliation. In addition, as a de facto economic sanction, the Chinese government canceled the export license for Canadian rapeseeds for quarantine reasons [17], and called for security precautions for travel to Canada [18](ケース9) (Case 9). In addition, Australia has eliminated Huawei products from Australia’s own 5G mobile communications network, and also has requested an international investigation into the source of the coronavirus. For security reasons, China urged its citizens to be cautious about studying abroad and traveling to Australia [19], and also imposed measures to restrict imports of Australian barley, wine, cotton, beef, lobster, and coal, etc. [20](Case 10). China is also implying that a sanction will be put in place against the UK where China would withdraw from the infrastructure project in the UK if the UK removes Huawei from its 5G network [21] (Case 14).

2. Means of Economic Sanctions

There are many means to impose political and economic costs (pain) against countries that are targets of economic sanctions. For example, typical sanctions include:

– Trade sanctions that restrict some or all of the exports and imports to and from the target country;

– The freeze of the target country’s assets accumulated in the imposing country;

– The suspension of business with the target country’s banks;

– Restrictions on external and internal direct investment;

– Financial sanctions, such as the reduction or suspension of development assistance for target countries; and

– Travel restrictions, which restrict the movement of civilians or government officials to and from target countries.

(1) Trade sanctions

As a recent global trend, the proportion of financial sanctions being used as a means of economic sanctions has increased [22]. Some of the reasons for this is that trade sanctions may partially invalidate the effect of trade due to smuggling or the starting of trade with third countries, while technological innovation has improved the possibility to monitor and track the flow of international funds, making it relatively difficult to take circumventive measures for financial sanctions such as asset freezes or suspension of business with banks. Unlike trade sanctions, financial sanctions make it easier to impose “smart sanctions” that target only certain individuals and groups, such as government officials, without hurting innocent citizens in the target country, making it less likely to be criticized by international public opinion, and more likely to avoid economic losses of countries themselves that have imposed sanctions.

Meanwhile, the most frequently used sanctions means by China in the last 10 years has remained trade sanctions (9 cases). Of these cases, eight measures were taken to restrict imports from target countries (Cases 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, and 17), and one measure (Case 1) to restrict exports to target countries. In addition, five of the eight import restriction measures have restricted imports due to “quarantine problems.” China’s sanctions are also characterized by the fact that they are not based on legislation, but they are imposed by arbitrary and opaque operations of existing systems (Cases 2, 3, 9, 10, and 17). “Symbolic industries” tend to be deliberately selected as items subject to import restrictions for sanction-target countries. Typical examples include Norwegian salmon, Philippine bananas, Australian wine and beef, and Taiwanese pineapples.

(2) Restrictions on trade in services and boycott movement

In addition to limiting trade in goods, China has taken three measures to restrict the import of services and digital content from sanction-target countries, including the calling off of K-pop concerts in China, the suspension of NBA broadcasts, and the suspension of sales of apps such as TripAdvisor (Cases 6, 8, and 15). In addition, two cases have been confirmed in which the Chinese government has either instigated or tacitly permitted a consumer boycott of target country products (Cases 1 and 6). Although consumer boycott movements by the Chinese people are neither explicitly directed by the government nor legally binding, a method to mobilize the people indirectly through the affected national media is used [23]. Unlike import restriction measures, consumer boycott movement sanctions will also affect the sales of products of companies in the target country, which are being produced in China, and it is possible that the companies will suffer a greater loss.

(3) Travel restrictions

Following trade restrictions, China’s preferred means of sanctions is to restrict travel (six cases). Such restrictions on travel to specific countries are also a kind of restriction on trade in services. Of these, there have been five cases where restrictions have been put in place regarding the travel of Chinese tourists to target countries and for Chinese students studying abroad in target countries on the grounds of worsening security, and so on (Cases 3, 5, 6, 9, and 10). One case has restricted the entry of a certain person of the target country into China (Case 16). With the growing presence of Chinese tourists worldwide, the implementation of travel restriction measures will have a significant impact on inbound-related industries in target countries. Therefore, it will be a very effective means of separating the public opinion of the target country and effectively applying political pressure from the inside to the target government.

(4) Financial sanctions

Unlike the United States, which has the U.S. dollar that serves as an international settlement and storage method, and that frequently imposes sanctions such as asset freezes and financial transaction suspensions, cases where China has imposed financial sanctions are limited. Specifically, as a suspension of development assistance (Case 5), an indication of the withdrawal of an infrastructure investment project (Case 14), the withdrawal of sponsorship (Case 8), and sanctions related to inward direct investment, two punitive measures have also been confirmed against target country companies operating in China (Cases 6 and 12).

3. Impacts of Economic Sanctions

What impacts did the economic sanctions imposed by China have on China and target country markets? The following points out five cases (Cases 2 to 6) that were imposed by the mid-2010s, and uses the statistics available to confirm their impact.

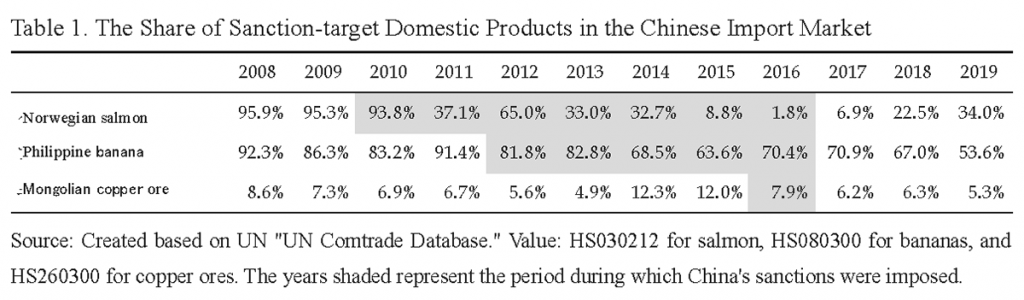

(1) Impacts of the import restriction measures

Looking at Norwegian salmon, Philippine bananas, and Mongolian mineral resources (especially copper ore) out of the cases concerning import restriction measures, the import share in China has been declining after the sanctions have been imposed in all cases (Table 1). In particular, before the sanctions, the import share for Norwegian salmon in China stood at 95%, but it fell sharply in line with the sanction impositions, falling to just 1.8% in 2016. Although not listed in the table, since the sanctions against Norway have been imposed, China has rapidly increased its imports of salmon from the Denmark-possessed Faroe Islands and the United Kingdom.

The share of imports of bananas produced in the Philippines also fell to over 60% due to sanctions, although the share of imports in China was above 90% just before the sanctions (during that time, imports from Ecuador and other sources increased). The share of Mongolia’s copper ore was limited even before the sanctions, but in 2016, when the sanctions were imposed, it fell by 34 percent year-on-year (during that time, copper ore imports from Peru and Chile increased). It should be specially noted that the impacts of the sanctions have been prolonged in all three cases, and the share for the aforementioned commodities have remained at low levels even after the sanctions have been lifted without recovering to the previous level of the market share.

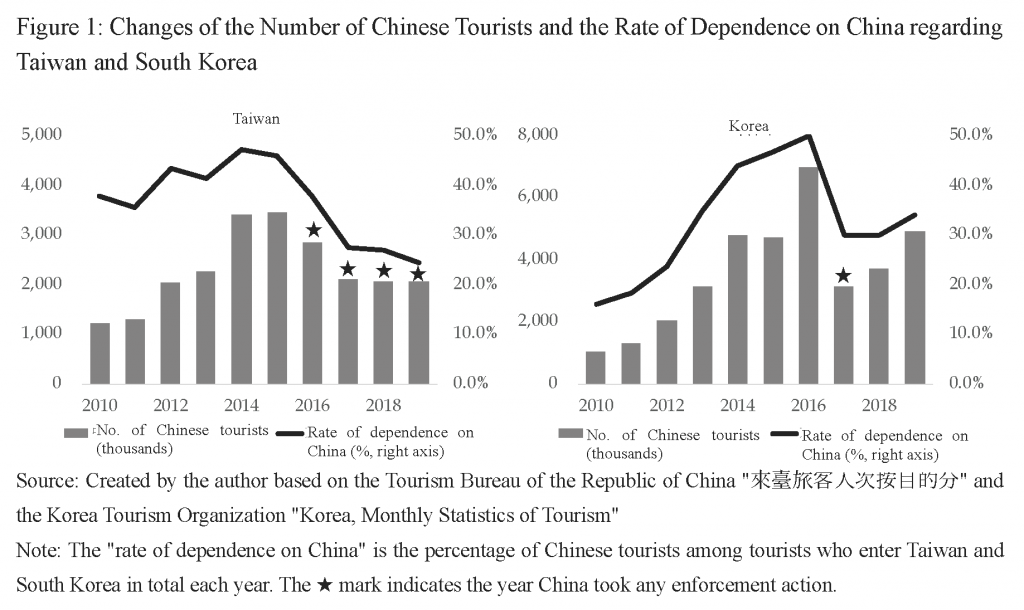

(2) Impacts of travel restrictions

The following cases of Taiwan and Korea will be used to determine the impacts of travel restrictions. Since the travel ban on Chinese tourists to Taiwan was lifted in 2008, the number of tourists each year has increased, rising from 1.23 million in 2010 to 3.34 million in 2015. When sanctions were imposed in 2016, the number of tourists fell to 2.85 million, and since 2017, it has consistently been around 2 million (Figure 1). Also, the percentage of Chinese tourists to Taiwan as a whole rose to about 50% in 2015, but fell to 24% in 2019.

The number of Chinese tourists also expanded significantly in Korea in the first half of the 2010s, reaching about 7 million in 2016 (50% dependence on China) just before the sanctions, but in 2017, when the sanctions were imposed due to the deployment of THAAD missiles, they fell sharply to around 3.12 million (29.9%), which severely affected the Korean inbound-related industries.

4. The Effectiveness of Economic Sanctions

Based on the theory of “Economics of Economic Sanctions,” the political and economic dynamics in the target country determine whether the target country offers concessions as a result of economic sanctions. [24]Specifically, if the country subject to sanctions is a democratic nation, and if economic sanctions are imposed, it will suffer economic losses and two groups will be created: a group that will put pressure on its government to make concessions to the imposing country, and conversely a group that will put pressure on its government to never give in to the sanctions. It is believed that the government of the sanctioned country will determine the degree of concessions by comparing the additional political gain (such as votes and contributions) gained by making concessions with the political loss. With this in mind, the following discussion will examine the effectiveness of China’s economic sanctions.

(1) Cases in which the target country made concessions

Among the cases of economic sanctions imposed by China, the target country made a certain concession to China in the following cases: Norway, the Philippines, Mongolia, and South Korea [25].

In December 2016, after six years had passed since the relationship with China had deteriorated, Norwegian Foreign Minister Brende visited Beijing to normalize relations with China and signed a joint statement saying “I will not support any action to weaken China’s core interests in the future.” Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi made an evaluation saying the Norwegian side had “deeply reflected on the reason why the bilateral trust relationship was broken [26].

Regarding the Philippines, the International Court of Arbitration ruled in July 2016 in favor of the Philippines surrounding the South China Sea problem, but the sanctions were gradually lifted by President Duterte, who took office in June 2016 and hammered out an appeasement policy with China. While he received many promises of economic assistance from China during his visit to Beijing in October of the same year, he also announced a statement at the summit meeting with President Xi Jinping that the South China Sea problem will be solved through talks between the countries involved. A meeting was also held with people from the Chinese industry where “putting an end to the U.S.” was declared in terms of military and business aspects. He showed a significant compromise toward the recovery of relations with China [27].

Moreover, in the ASEAN Summit Meeting in Singapore in November 2018, he raised controversy, saying, “China already owns the South China Sea [28]

With regard to Mongolia, which was sanctioned on December 1 by a visit of the Dalai Lama in November 2016, three weeks later on December 21, Foreign Minister Munkh-Orgil (at that time) expressed his regret over the negative impact on bilateral relations created by the visit, and expressed Mongolia’s position that it would not accept any visits from the Dalai Lama in the future. The China’s Global Times reported this as an “apology [29] .”

South Korea, which has been subject to extensive sanctions by the deployment of THAAD missiles, agreed with China at the end of October 2017, five months after President Moon Jae-in took office, who attaches importance to improving relations with China, on the “three no’s” that are “South Korea will not deploy additional THAAD missiles,” “will not participate in U.S. missile defense,” and “will not develop Japan-U.S.-South Korea security cooperation into a military alliance” to improve the relationship with China [30].

As previously mentioned, the target for sanctions against Norway is salmon, against the Philippines is bananas, against Mongolia is mineral resources, and against South Korea is K-pop. These are all “symbolic industries” for the target countries. By pinpointing these industries, it is possible for China to maximize public interest in the target country, and to effectively create a situation where the targeted industry will put pressure on the government to make concessions to China. In fact, in the case of the Philippines, reports have been made that banana exporters who were subject to the economic sanctions have put pressure on the Philippine government to improve the situation [31].

(2) Cases in which the target country has not made concessions

Of the economic sanctions imposed in the 2010s (Cases 1 to 9), Japan, Taiwan, the United States, and Canada did not yield to China’s pressure. Facing the export restrictions of rare earth, Japan tried to resolve bilateral issues through diplomatic channels, while in March 2013, it filed a lawsuit against China to the WTO as did the United States and the EU. In August of the following year, the WTO Senior Committee issued a report acknowledging Japan’s assertions [32] , and China abolished the export restrictions in January 2015 in accordance with the recommendations of the Senior Committee [33] Facing China’s travel restrictions after the birth of the Tsai Ing-wen administration, Taiwan aimed to offset some of the negative impact of the sanction measures by attracting tourists from Malaysia, Indonesia and other countries [34]. In the case of the United States and Canada (retaliation against Sections 301 and 232 of the Trade Act), China still continues its sanctions. Note that in those cases confirmed after 2020 (Case 10 and later), there are no cases where the target country has made concessions in order to settle matters with China, even though China’s sanctions continue to remain in place. Based on the theory of Economics of Economic Sanctions, these cases may be regarded as those where the political loss of making a concession to China exceeded the gain for the government of the sanctioned country.

With the exception of the case regarding Japan, in which China lost its case in the WTO, China has not confirmed cases of its own withdrawal of sanctions even the sanctions have failed. Why is that? The ideal form of economic sanctions would be that the target country makes a concession and corrects its policies and positions in the direction desired by the imposing country as a result of political and economic pain dealt (or threatened) to the government, industry, companies and individuals of the target country. On the other hand, even if a concession cannot be drawn out, the imposing country (China) may achieve a separation of public opinion of the target country and the weakening of the target country’s government through the imposition and continuation of economic sanctions. Or, it may enhance national prestige and achieve political gains in the imposing country itself, such as gaining support for the administration [35]. Based on these ideas, it may be reasonable for China to continue to impose economic sanctions, whether or not the target country makes concessions.

5. Conclusion: Geoeconomic Implication

This paper examines the characteristics, impact, and effectiveness of economic sanctions imposed by China since 2010. Based on the discussions so far, the following sections describe some of the geoeconomic implications.

First, China has imposed sanctions by carefully scrutinizing its target countries and measures to maximize the political and economic impact that the economic sanctions deal to the target countries. Especially in recent years, there have been an increasing number of cases in which the “symbolic industry” of a target country is targeted, hoping that the “public opinion,” which is the Achilles heel of democratic governments, will be cleverly divided, and that some of the anger of the industries suffering from the pain caused by the sanctions will be directed toward the target country’s government.

Second, China is imposing economic sanctions in such a way that its industry and consumers do not suffer major economic losses. For example, China’s frequent travel restrictions on certain countries can severely damage the inbound related industries of the target country, while the vast majority of Chinese tourists only temporarily lose one of their destination options, and can also travel to other alternative destinations to satisfy their immediate needs. As noted in the cases of salmon in Norway, bananas in the Philippines, and copper ore in Mongolia, China has succeeded in quickly substituting imports from target countries with imports from third countries when it imposes import restrictions.

Third, it is not surprising, but China does not easily withdraw its once-imposed economic sanctions. Even in the cases discussed in this paper, China has never withdrawn its own imposed sanctions, except in cases where the target country has made concessions to China or in cases where the WTO has determined violations of the measures. In this regard, it is necessary to promptly normalize the currently dysfunctional WTO dispute settlement procedure and to establish an environment that will allow China to resolve problems at the WTO rather than at a bilateral level if China imposes sanctions in a manner that would violate the WTO Agreement. Although some issues exist, it has been pointed out that China has been correcting its measures in accordance with the WTO’s recommendations in the event of a defeat in the WTO dispute settlement procedure [36].

Fourth, there are limitations in responding to the risks of China’s economic sanctions, relying solely on the current WTO rules. As the reasons behind this, China has imposed (1) sanction measures using the exception of the WTO rules as an excuse (e.g. measures on the grounds of environmental protection, resource conservation, quarantine issues, or the protection of public morals); (2) sanction measures in a manner where it cannot be necessarily proved that there is direct involvement or instructions by the government(e.g. instigation or tacit permission of consumer boycotting through state media), or (3) sanction measures in areas outside the scope of the WTO rules (for security reasons, such as a call for caution regarding travel and studying abroad to certain countries, announcement of suspension of loans, and withdrawal of sponsors). In addition, there may be no possibility of correcting said measures even by using the WTO dispute resolution procedure. In addition, even if the measures are clearly in violation of the WTO Agreement, it may take several years for said violation to be confirmed and for China to correct the measures, resulting in the target country having to continue to bear the pain of the sanctions.

Fifth, in order to minimize the risks of economic sanctions of China on the assumption of the above, it is necessary not only to maintain as good a bilateral relationship as possible with China from a pragmatic perspective, but also to take measures to diversify sales and procurement partners so as not to excessively increase reliance on China in the areas of goods, money, services, people, and technology.

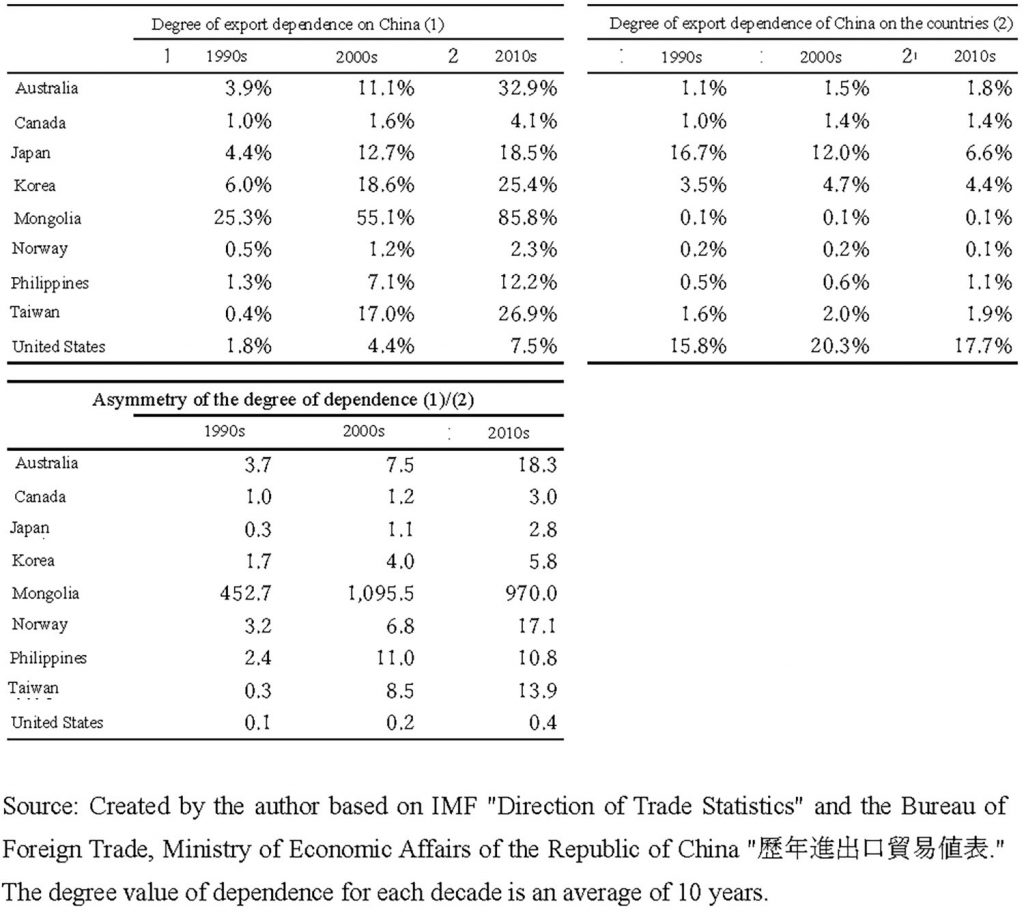

Table 2 summarizes the degree of export dependence on China concerning the countries in the cases detailed in this paper, the degree of export dependence of China on said countries, and the changes in the dependence ratio of China and said countries. It can be read from the table that since the 1990s, countries’ dependence on China for exports increased without exception as China’s domestic market expanded. In particular, the countries that are geographically close to China are generally highly dependent, with Australia, Taiwan, and South Korea exceeding 25% and Mongolia exceeding 85%. On the other hand, China’s export dependence on the U.S. is high at 17.7%, but even dependence on Japan and Korea is at around 5%, and on all other countries it is low at less than 2%.

Based on the above, it can be said that there is a large “asymmetry regarding the degree of export dependence” between China and the countries. For example, the ratio of the degree of export dependence shown in the lower left of Table 3 shows that the United States is the only country that is less than 1, i.e., has a lower dependence on China than the dependence of China on it, while other countries rely on China very asymmetrically. In addition, in almost all the countries, this ratio has increased significantly over the past 30 years, and the asymmetry of the degree of dependence has kept increasing. Of course, the situation is not uniform by industry and by item, but in other words it can be said that “asymmetry regarding the effectiveness of economic sanctions” is expanding.

Finally, in addition to activities at each national level, it should also be considered to develop multilateral mechanisms in cooperation with other countries to enhance toughness against China’s sanctions risks. In particular, since 2020, China has institutionalized economic sanctions that had been implemented in a vague manner, including the enforcement of the Export Control Law to regulate exports of strategic goods under a permission system and to prohibit exports to specific companies, and the enforcement of the Rules on Blocking Unjustified Extraterritorial Application that allows China to claim damages against foreign companies which have joined in sanctions against China. The sanctions risks faced by the countries previously discussed are increasing further. Already in the Indo-Pacific region, the following points have started to be established or considered:

– Framework for infrastructure support by Japan, the United States and Australia as an alternative to China’s economic support under the Belt and Road Initiative concept;

– Framework for vaccine support by the Japan-U.S.-Australia-India Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) as an alternative to China’s vaccine diplomacy; or

– Framework for consultations to ensure a stable supply of important materials, such as rare earths, depending on China [37] . It is required that these activities will be more generalized and that countries that share the same concerns consider ways of an information sharing mechanism, stable supply mechanism, and mutual relief mechanism for emergencies to address the risk of China’s economic sanctions.