China’s Growing Engagement in the Pacific Islands: Unveiling Opportunities for Island Nations

China’s influence in the Pacific Islands has been growing steadily in recent years, extending beyond economic aspects to encompass security concerns. This has naturally elicited a response from Western democratic powers, who are undertaking various initiatives to preserve and expand their presence in the region. Consequently, the Pacific Islands have become a focal point of friction between these Western democratic powers and China. Amidst these geopolitical circumstances, the Pacific Island countries have adopted a stance of neutrality that is encapsulated in the principle of “friend to all, enemy to none,” thereby pursuing a strategy of balanced diplomacy.

How does the growing influence of China in the region and the resulting friction between Western democratic powers and China affect the Pacific Island nations? This question can be examined from the dual perspectives of “the opportunity provided by China” and “the threat posed by China.”

From the perspective of “the threat posed by China,” the concern is that China may be orchestrating a “debt trap,” and the expansion of Chinese aid could lead to the erosion of sovereignty of the Pacific Island nations. While there is currently no direct evidence indicating that the sovereignty of these nations has been compromised owing to China’s alleged debt trap or that such a trap is indeed being laid, its possibility cannot be entirely dismissed. The narrative of “the threat posed by China,” which is predicated on the potential dangers of a debt trap, has been consistently promulgated by Western democratic powers not only in this region but globally. Therefore, further elaboration would be redundant.

This commentary focuses on “the opportunity provided by China.” It aims to elucidate how the expansion of China’s influence could manifest as opportunities for the Pacific Island nations.

Economic opportunities

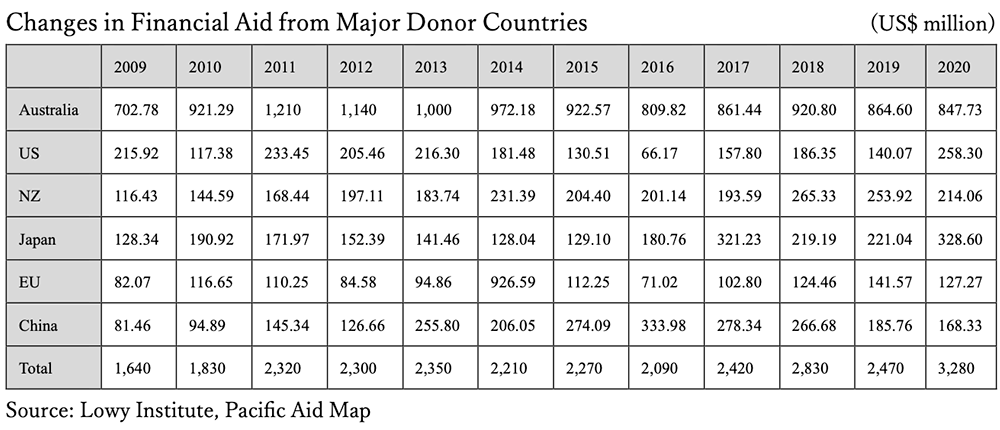

In addition to the aid provided by the traditional donors, such as Australia, New Zealand, Japan, the United States, and France, there has been a substantial influx of Chinese aid to the region since the mid-2000s. Moreover, Western nations have increased their contributions in a bid to counterbalance the surge in Chinese aid. As indicated by the following table, there has been a steady annual increase in the cumulative aid received by the Pacific Island nations, from approximately $1.65 billion in 2009 to an estimated $2.83 billion in 2018.

The friction between the two sides has inadvertently spurred the development of infrastructure, regardless of its necessity. Chinese aid, with its emphasis on infrastructure development, has been warmly received by the Pacific Island nations owing to its swift implementation and China’s lenient aid conditions. Conversely, Australian aid, which represents the largest contribution in the region, focused primarily on governance improvement until the mid-2010s. In fact, approximately 36% of the Australian aid to the Pacific Island nations in 2017 was allocated toward governance improvement (DFAT 2017). However, in response to China’s development of infrastructure in the region, the proportion of Australian aid dedicated to infrastructure development was increased from approximately 16% in 2017 to around 24% in 2019, whereas the proportion allocated for governance improvement declined to about 26% in 2019 (DFAT 2019). Additionally, in 2018, Australia announced the creation of a $2 billion infrastructure fund as a part of the Pacific Step-up initiative, which was aimed at enhancing its diplomatic ties with the Pacific Island nations. The fund has been operational since 2019.

Political opportunities

Until the intensification of China’s involvement in the mid-2000s, Western democratic powers were the primary donors for the Pacific Island nations, with Australia providing a significant proportion of the total aid, particularly in the South Pacific. During this period, Australian aid represented approximately 50% of the total aid received by the Pacific Island nations and approximately 70% of the aid provided to the Melanesian nations (Lowy Institute, Pacific Aid Map). Essentially, Australian aid served as a vital lifeline for the Pacific Island nations that needed assistance, which made it challenging for these nations to strongly voice their grievances against Australia. In fact, the island nations critiqued Australia’s interventionist approach, viewing it as a perpetuation of the colonial-era power dynamics of the rulers and the ruled, an imposition of Australian norms, and a form of neocolonialism. Although a certain degree of heightened nationalism could be observed, their dissatisfaction did not translate into potent oppositional actions. Further, Australia’s influence within the region remained undiminished.

However, with the increase in aid from China and the consequent decrease in dependence on Australia, Pacific Island nations have gained the capability of not only criticizing Australia’s approach but also mounting robust oppositional measures.

For instance, in the aftermath of the 2006 coup in Fiji, economic sanctions were imposed on Fiji by Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Japan, who cited the military regime’s prolonged failure to conduct elections. Moreover, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), an assembly comprising the Pacific Island nations, Australia, and New Zealand, suspended Fiji’s membership. Countries, including Australia, had expected Fiji to adhere to their directives and promptly hold elections, as it had previously.

Following the coup and Fiji’s subsequent failure to conduct elections, Australia’s financial aid to Fiji decreased from approximately AUD 31.2 million in 2006 to roughly AUD 27.6 million in 2007. In stark contrast, as reported by the Lowy Institute, Chinese aid increased substantially from about USD 1 million in 2005 to roughly USD 160 million in 2007 (Hanson 2008). This dramatic surge in Chinese aid led to a perceptual shift within Fiji, with China being lauded as a savior and a nation that respects Fiji’s sovereignty. Concurrently, there emerged a sentiment that Australian support was no longer needed (Hayward-Jones 2011). Consequently, Fiji adopted a confrontational stance toward Western democratic powers and defied their anticipations. It reinforced its China-centric Look North policy and, in 2013, established the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF). The PIDF, which was formed as a counterweight to the PIF, notably excludes Australia and New Zealand from its membership. Fiji further articulated its stance by declaring its non-participation in the PIF General Assembly as long as representatives from Australia and New Zealand were in attendance. This stance was maintained, with the Prime Minister of Fiji refraining from participation in the General Assembly until 2019.

Thus, the expansion of Chinese aid has presented an opportunity for the Pacific Island nations, which had hitherto been unable to effectively resist Australian influence, to break free from Australian dominance and affirm their sovereignty more assertively.

References

- DFAT (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). 2017. Australian Aid Budget Summary 2017-2018, Canberra: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

- DFAT (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). 2019. Australian Aid Budget Summary 2019-2020, Canberra: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

- Hayward-Jones Jenny 2011. Policy Overboard: Australia’s Increasingly Costly Fiji Drift. Sydney: Lowy Institute.

- Lowy Institute, Pacific Aid Map.

(This is an English translation of a Japanese-language essay dated November 16, 2023 in which SEGAWA Noriyuki, Professor at Kinday University, analyzed big power posturing in Oceania.)