“Pro-American yet Autonomous” in a multipolar era

Introduction

This article offers an independent examination of the global power changing relations within Eurasia and Japan’s position because of China’s rise, considering the Japan-United States (US) alliance and Japan’s relationships with the major Eurasian powers. Further, hopefully, it will be possible to position Japanese diplomacy toward Eurasia as a catalyst for pro-US yet autonomous Japanese diplomacy. Although the significance of “autonomous” is relative, it means that Japanese diplomacy must adopt a more flexible and multifaceted mindset than today, given the number of unforeseeable factors. Compared to the US, Japan is a nation with a different geopolitical position, national strengths, and national characteristics. Therefore, the regional and international perceptions differ between Japan and the US. Although the “multipolar worldview” is shared by the EU member states, China, Russia and other East Asian countries. the Japanese and the US media tend to be reluctant to use this term.

However, perceptions of “US hegemony” are receding. To what extent do we consider this at face value? Although the Japan-US alliance is the cornerstone of Japanese diplomacy, we must consider that global perceptions of the international order are changing in response to China’s rise. Nevertheless, few people believe that China’s rise will reach parity with the US in terms of overall strength in the next five to ten years. There remains a strong view that the US is the global hegemon and must remain the world’s police even if its influence is on the wane. Nonetheless, the gap between the US and Chinese power is narrowing. This is apparent when we consider the significant turbulence in the US, such as during the Trump administration. In a public opinion survey conducted by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) at the end of 2020, immediately following the formation of the Biden administration, over half of the Europeans felt a strong sense of crisis about the shaking state of American democracy.

At this turning point, it is essential to rethink Japanese diplomacy and the world from a geopolitical standpoint. This is because, geopolitically, Japan could find itself caught between the US and the Chinese powers. It could easily become a dependent variable within the framework of US-China relations. To what extent can we act as intermediary over those intricate relations? Can Japan show its diplomatic insight? The ideal of Japanese diplomacy is to play an independent role as a bridge between the two sides. This opinion is often met with following response: “that’s sound in theory but impossible to achieve in practice.” It certainly will not be easy. However, should we give up, diminish ourselves, and settle for being a junior partner to the US because it is difficult to become an intermediary or a bridge? This raises an issue that reaches the heart of Japanese diplomacy. It may be a matter of lifestyle for individuals, but what about the nation?

Even if it might seem idealistic, I would like to consider how Japan can play an even more important political role in Asia and globally—to use a somewhat rhetorical expression, I would say “Pro-US yet autonomous diplomacy.” Nothing is better than having an independent and reliable friend. It is only natural for independent people and countries to have differences of opinion. However, if a relationship of trust is established, it should be possible to cooperate on a single goal astutely—it is proof of a powerful and dependable allied.

This scenario would require Japanese diplomacy to be increasingly flexible. Subsequently, it is essential to hone one’s insight sufficiently to convince neighboring countries and the world to conduct and communicate this insight effectively. One might call this “insight diplomacy.” This should not be limited to defense buildup discussions or arms races. Military realism is rousing, but the devastation in Ukraine illustrates today’s tragedy as its result. What we need in diplomacy now is political realism. In this context, while statements by officials with field experience are valued considerably, the current expectation is the appearance of states people and politicians possessing high levels of foreign policy insight. Japan is a trusted, safe country that numbers among the world’s leading nations in terms of overall strength. It has a good image based on strong credibility and a national brand. Therefore, it is neither rash nor reckless for a country to have its long-term, broad vision for the stability of the international order (=global governance) and be able to respond freely. If it is seen to waver in making positive commitments at the cost of stability, it will set back the world’s expectations for Japan.

“It’s Time to upgrade Japanese Diplomacy!” – Indo-Pacific and East Asia are other options, but is there no other option in the form of Eurasian credibility diplomacy? (refer to “Ugoke, Nihon gaikō [Move forwards, Japanese Diplomacy!”, Diplomacy, Vol. 1, 2010).

1. Eurasia’s geopolitical significance

A Different View of the Map – Reality of Japan’s Geopolitical Location

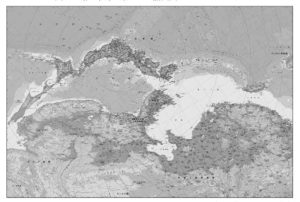

First, Japan is a Pacific country and part of the Eurasian continent. We usually view Eurasia (the Asian continent) as being beyond the Sea of Japan. Moreover, there is a strong tendency to view relations with the United States, which is much further away across the Pacific Ocean, as being closer than those with China and the Korean Peninsula just across the Sea of Japan. I believe this to be unnatural. Despite having East Asian geographical and cultural attributes, the Japanese foreign policy has a twisted structure. It is more politically and diplomatically affine with the United States, far away on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. This has been a historical tradition since the policy of the Meiji era “out of Asia and into Europe,” but how long can this continue in the face of China’s and Southeast Asia’s remarkable growth? Let us take a look at Map 1.

Map 1: Japan Sea Rim and East Asian countries (Toyama-centered orthographic map)

Reprinted from a map created by Toyama Prefecture

Maps have different meanings depending on how you look at them. Map 1 is the famous “upside-down map” published by Toyama Prefecture. Although the Sea of Japan divides Japan from continental Asia (Japan and China) from the standpoint of diplomatic strategy, in this map, it looks more like an “inland sea” sandwiched between the continent and Japan. It is more natural to view Eurasia and Japan as a single economic and customs zone. This map shows Japan in a different geographical position from the familiar Mercator map, which has the Pacific Ocean in the center of the map on an east-west horizontal axis.

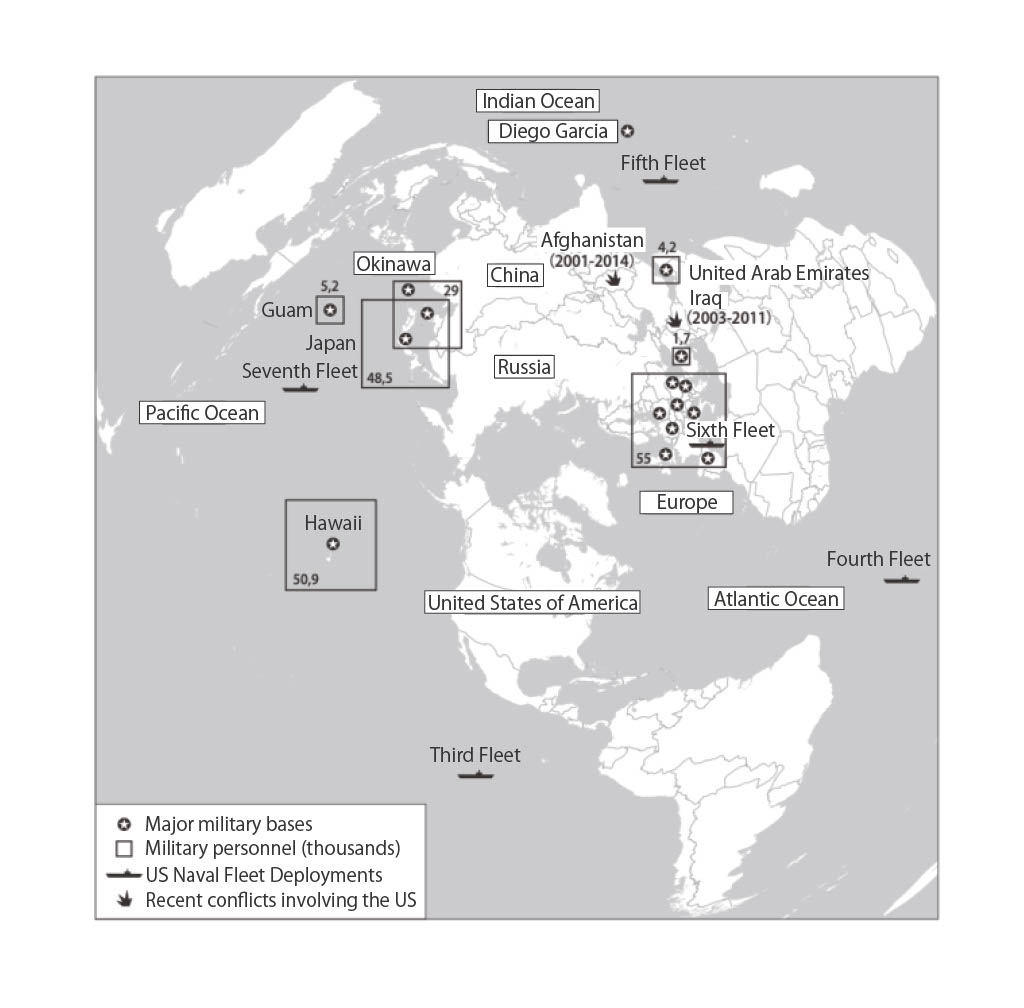

Moreover, Japan is positioned as a “buffer state” between a continental (land power) and a maritime power (sea power). As seen from the continent looking out over the Pacific Ocean, Japan is a breakwater and fortress. Conversely, the Pacific side is a bulwark and outpost against continental advance. In other words, Japan is a double-edged breakwater from the perspective of the continent and the Pacific Ocean. Let us examine Map 2. It shows the US military defense force deployments worldwide, as seen from above the North Pole. They form a security network surrounding the Arctic Ocean. The US global military deployments span Hawaii, Okinawa, Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, several military bases in Europe, plus the Fourth Fleet in the Atlantic, the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean, the Third and Seventh Fleets in the Eastern and Western Pacific, and the Fifth Fleet in the Indian Ocean. In this sense, Okinawa and Guam occupy vital positions in defense of the Western Pacific and the Asian continent.

Map 2: US military deployments viewed from the North Pole

Produced from Grand Atlas 2017(Courrier International), p. 115

Russian military ports and naval bases are situated on the other side of the Arctic Ocean. The strategic positioning of the Arctic Ocean is diametrically opposed depending on whether the US-Russian relations are hostile or friendly. The Sea of Japan holds the same geopolitical significance. As global warming makes the Arctic Ocean more practical, new developments in relationships between the US, China, Europe, and Russia are also possible.

Expanding Options for Japanese Diplomacy: Eurasian Perspectives

Considering these two maps, it becomes possible to consider Japan’s geographic position in terms of politico-strategy—Japan’s geopolitical position; it is also about understanding the beginning of Japanese diplomacy. To conclude immediately, Japan’s position can be unstable because it is caught between major powers, but it can also benefit by handling this situation properly. Developing autonomous diplomacy has many constraints, but even if Japanese diplomacy has been characterized by altruistic diplomacy, it has negative aspects as well as positive, depending on the circumstances. Japanese diplomacy is strongly influenced by the relationships between the land powers (Eurasian powers, China, and Russia) and sea powers (maritime powers, the US and Britain) flanking it. The relationship between these two groups is a major determinant of Japan’s existential value and diplomatic positioning. In other words, Japan is a subordinate variable affected by the relationship between both groups. During the Cold War, when “sea power” was overwhelmingly strong, alliance with the sea powers was the only lifeline for Japanese diplomacy. Nevertheless, as the relationship between both powers grows more evenly matched, oscillating between confrontation, negotiation, and proximity, Japan must be prepared to take a more flexible stance. I think this is true realism.

Considering power politics, if the relationship between the US and China remains cordial, the Japanese archipelago will become a central region for transportation and commerce. Should tensions between the two powers escalate, the ongoing crisis in Ukraine will no longer be someone else’s problem. Again, Japanese diplomacy has always been strongly other-directly. A sincere, friendly relationship between both powers is certainly the best scenario for Japan. However, Japan can be said to have historically performed considerably well. It did not become a divided nation like Poland, Germany, or the Korean peninsula. Historically, Japanese diplomacy has been committed to stability and prosperity under the aegis of US power and has succeeded in bandwagon diplomacy. Before the Edo period, Japan was a member of the Greater China region through tribute and trade, a land power. Following China’s decline, Japanese diplomacy was based on an alliance with the United Kingdom and the United States, the leaders of modernization and sea powers.

An exceptional and regrettable period was from the early 1930s to the end of World War II. Despite strengthening its continental expansionist policy with Western help, Japan overextended itself in clashing with the Western powers. However, this could shake the foundations of Japan’s post-modern diplomacy should China transform from a regional power to a nation exerting a global influence (power transition). Japan will be forced to deal with a different international structure in Asia. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the changing situation in Eurasia. The meaning of “power transition” is surprisingly important to Japan. This was in the 1990s and early 2000s, the post-Cold War period, when Japanese diplomacy turned its attention to Eurasia. Subsequently, Japan’s Eurasian diplomacy became unenterprising from its position of prioritizing diplomacy with China and North Korea. From a long-term perspective, future trends in Eurasia and the response of Japan and the Japan-US alliance to these trends are unclear. As described at the beginning of this article, it addresses whether Japan’s geographical position between sea and land power can be considered in its politico- diplomatic view points and whether Japan’s diplomatic options can be further expanded by revitalizing its Eurasian diplomacy. It is also a simple question of whether Japan can remain a “detached Eurasian peninsula” amid the structural changes in the Eurasian international environment caused by the rise of China.

2. External Factors in the Transformation of the Eurasian International Environment

Waning US Influence

We list two external factors driving the transformation of Eurasia’s international environment. Popularly called “power transition,” it refers to the rise of China, but its inverse is the waning influence of the United States. The “New World Order” proposed by President George Bush, Senior immediately following the end of the Cold War failed to establish a clear vision. However, the rapid growth of high-tech sectors due to the IT revolution was the beginning of the US becoming a major power in the military, economic, and scientific fields. During the second term of the Clinton administration and the beginning of the George W Bush era, the US transitioned to an “era of hegemony.” Nevertheless, the Iraq War was the second most painful experience for the US after the Vietnam War. The US has since been forced to take an extremely cautious attitude toward intervention in other countries and deploy its troops overseas.

Meanwhile, Russia has revived itself through resource exports, and China has achieved remarkable economic development; they have drawn closer together in Eurasia. The Obama administration shifted its policy toward a “Rebalance to Asia” in response to China’s expanding influence in 2011–12. This has not succeeded in stopping China’s maritime expansion and North Korea’s nuclear missile development. However, the Trump administration’s hard-line stance toward North Korea and China has caused considerable anxiety worldwide that US policy might be implemented consistent with Presidential rhetoric. There were strong opinions within the administration that this should be suppressed; the US-North Korea talks are a manifestation of this. Despite being different in appearance, Biden’s diplomacy is a continuation of the previous administration. In this sense, the unipolar system under the US-style “liberal democracy” and the coexistence system of powers with shared worldviews resulting from the multi-polarization in Eurasia will continue. I once considered this conflict as a clash between two universalisms. I said that it would persist at least until the end of the first quarter of this century (see my works, “Post-Empire: The Clash of Two Universalisms,” Surugadai Shuppan, 2006; and “US-European Alliance and Conflict,” Yuhikaku, 2008).

Transformed Geopolitical Significance: Birth of the Arctic Sea Route

Another factor contributing to Eurasia’s transformation is the change in the natural environment and the accompanying changes in the strategic map. The geopolitical position of the Sea of Japan is expected to become more significant as a strategic transportation route for China, Japan, and South Korea. This is the birth of the Arctic Ocean route. China’s ambitions for Arctic shipping routes, which will become navigable year-round due to global warming, are remarkable. This issue also marks a shift in geopolitical thinking in Eurasia. This means that Eurasia will no longer be a continent with its northern exit blocked by the Arctic Ocean but a new Eurasian island surrounded by the sea on all sides. The coastal areas around the Arctic Ocean are strategic points for Eurasian countries, as shown by the location of the US military bases on the map and for trade and transportation routes.

In other words, in addition to the transportation routes surrounding Eurasia through the Pacific and East China Seas, the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic Ocean, the wide availability of the Arctic Ocean route will redraw the map for new transportation routes in Eurasia. In addition to the previous geographic routes along an east-west axis, the development of vertical routes extending north-south will amplify the new geopolitical significance of Eurasia. Consequently, the Eurasian power map could be significantly modified. Such a scenario would likely require a new axis in Japan-Russia and Japan-China relations framework. Will this be an “open Eurasia”? The answer will depend on the future efforts of the countries involved.

3. Distribution of Multi-Layered Spheres of Power

Three “Spheres of Power” through the Multilateral Cooperation Framework and India

Roughly speaking, international relations in Eurasia are evolving through the merging of five spheres of civilization and three spheres of influence. The five spheres of civilization are Confucianism and the Chinese world, Orthodox Christianity, Christianity, modern democracy and market economy, Hinduism, and Islam. The three spheres of influence are China, Russia, and the EU, each with its cohesive power. As a matter of terminology, the term Russian “sphere of influence” has become common due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, this tends to be used in the sense of a military defensive sphere. Therefore, I use “sphere of influence” without strictly distinguishing between military and non-military powers.

The spheres of influence were limited to three because of some question as to whether the Middle East region and India as a major power, can be called a sphere of influence, although it is a sphere of civilization. These two regions were omitted because no power has a strong, cohesive sphere of influence over the surrounding area. Although the Middle East region is broadly categorized as an Islamic religious sphere, its internal situation is complicated and divided, with religious conflicts often crossing national boundaries, and there remains no clear existence of a cohesive national power. Moreover, amid friction with China and the Muslim world, India does not have the power to unite with its neighbors as other countries in the center of their spheres of influence do. However, it is making its presence felt in diplomacy as a major nation. Nevertheless, the EU lacks cohesive power but is a sphere of influence that does not, in theory, assume a core power because it uses democracy as its integrating principle. Undoubtedly, Germany and France are its central forces. Nonetheless, the EU possesses considerable influence and could be called an economic power, albeit not military power, and a force that disseminates its governing principles and other modes of social norms and order—normative power. In Eurasia, the three spheres of influence (China, Russia, and the EU) and India compete and cooperate. As a sea power, the US is attempting to develop a new axis of diplomacy with each administration. Although not the theme of this book, I believe that the US can be described as a normative power, as it has been called a powerhouse of ideas; however, the range of the US is not regional but global and universal. The EU’s range was regional but is steadily expanding its scope to the global scale.

China’s Aim for “A Community with a Shared Future for Mankind”

First, the rise of China is symbolized by the “One Belt, One Road” concept proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013. It is a win-win concept of cooperation and interdependence encompassing political, economic, and cultural fields, but each area and plan is not necessarily closely connected to the others. Although it is a vague concept of China’s sphere of influence and power, this “Chinese dream” proposed by Xi Jinping indicates China’s strategic intent, which has brought expectations, anxiety, and alarm to neighboring countries and the entire Eurasian region.

Its core encompasses a vast area stretching from Eurasia to Africa. In Japan, discussions concentrated solely on the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), led by China, but that is only part of this concept. One Belt, One Road is China’s plan to expand its sphere of influence and power throughout Eurasia, right up to the EU member states. Although China calls for cooperation in the “five connectivities” (policy, infrastructure, trade, investment, and people exchanges), the reality is an accumulation of bilateral relations with China as the hub, which China calls “global governance” or “multilateral relations.” The language may be the same as in the US and Europe, but its substance is interpreted in Chinese.

In 2017, China established its first overseas supply base in Djibouti, East Africa, at the meeting point of the Eurasian and African continents. It has acquired rights to use ports in over 30 key locations along the sea lanes connecting China with oil-producing Middle Eastern countries and Europe. It also has the deployment of military bases in its sights. As for securing sea lanes, the use of the Arctic Ocean is also linked to the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, dubbed the “Silk Road on Ice.” In January 2018, China released its “White Paper on the Arctic Policy.” The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) on the security front and the “+1” with Central and Eastern European countries, including EU member states, on the economic platform are Chinese-led multilateral frameworks.

Russia’s Prestige Diplomacy

Second, what about the world as seen from Russia and Central Asia? Since the 1990s, many books on geopolitics have been published in Russia, analyzing international affairs from a Russian perspective. Historically, Russian identity is characterized by its identification with Westernization and a reaction to that identification. Russian diplomacy is characterized by a major power based on diplomatic skills and military power rather than economics. Putin’s diplomacy has no long-term vision but is said to prioritize restoring foreign prestige. The invasion of Ukraine, begun in February 2022, was intended to restore Russia’s “imperial” glory and prestige in response to NATO having nearly entirely encompassed the surrounding region. The beginnings of anti-US and European diplomacy under the Putin administration could already be seen during the controversy surrounding the Iraq war but became more pronounced after the “Color Revolution” of 2003–2004 and the EU/NATO’s eastward expansion. Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference in February 2007 criticized the US and Europe, reminiscent of the Cold War. Russia’s military intervention in Georgia during the 2008 conflict was the beginning of the events that led to the 2014 Ukraine conflict.

The Ukrainian conflict provoked economic sanctions by the US and Europe, dealing a heavy blow to Russia, which became more economically dependent on China, particularly on exports of liquefied gas and crude oil to China. Closer ties between China and Russia can potentially complicate geopolitical power relations in Eurasia. When French President Macron proposed a new “European Security Organization” to Russia in September 2019, it was intended to drive a wedge between China and Russia in Eurasia. Although public sentiment toward Russia and China in Central Asia is complex, Russia intends to strengthen its relations with the former Soviet republics and the Middle East. The Eurasian Economic Union (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (the five countries mentioned above plus Tajikistan) are two central regional organizations. Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan are not members of either, but they each maintain close bilateral relations with Russia. The Central Asian countries are pro-Russian, but the region is also relatively friendly with China. Like Japan, the Caucasus region, geographically sandwiched between the power blocs of Russia and the West, has always faced a delicate diplomatic situation. They have, respectively, adopted positions of neutral and balanced diplomacy (Azerbaijan), pro-Russia (Armenia), and pro-US-European (Georgia), with varying responses depending on their geographic and cultural distance from Russia.

The EU’s aim for normative power

Third, the EU policy lacks a comprehensive “Eurasian policy.” However, the EU’s Eurasian policy can be considered an extension of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP). Part of the Eastern Expansion, the “Eastern Partnership” is also part of the ENP. It is a policy of expanding a broad sphere of influence reaching Ukraine and the GUUAM countries (Georgia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Moldova). However, in the EU’s case, conditions for membership include criteria centering on democratization and a market economy (Copenhagen Criteria). Nevertheless, the Neighborhood Policy also sets various detailed attainment goals based on European criteria for modernization, democratization, and human rights.

The EU calls itself a normative power, referring to its position of prioritizing contributing to establishing a common foundation for national principles and standards—influence in the form of soft power. The EU has historically had an affinity for Russia as part of its policy of balanced diplomacy with the US and China. There is a strong pro-Russian tendency in Germany, in particular. It is well known that former German Chancellor Schröder is an executive of an affiliate of the Russian oil company Gazprom. However, its transformation into an energy superpower and diplomatic offensive since the turn of the century under Putin’s regime has heightened alarm among the EU nations. Russia’s staunch military occupation of the Crimean Peninsula and its hybrid strategy in the Ukrainian civil war has imposed an image of the Soviet Union=Russia as a military power. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was an inevitable consequence of this.

However, Europe’s view of China is centered on the admiration for the country’s long history and its economic interests. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly wary of the aggressive aspects of China’s “One Belt, One Road” concept. Thus, the EU’s policy toward China can be summed up as one of proximity and caution. Nonetheless, from the “Strategy for a New Partnership between the EU and Central Asia” in 2007, the EU has been striving for closer relations with Central Asian countries to support and cooperate in areas of democracy promotion, human rights and good governance, security and counterterrorism, and energy and infrastructure transportation.

An Open Eurasian + Pacific Community: Insight for a role of Bridge to Eurasia

There is no definitive, ingenious answer to how Japan should respond to the current situation in Eurasia described thus far. As discussed, Japan is in a geopolitical position where it is forced to conduct heteronomous diplomacy. How can it ensure diplomatic independence in such a situation? Japan should pay more attention to the geopolitical power politics of Eurasia. However, the current US policy has its limitations. It is one of “intervention and hedging.” Despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the US could not get directly involved, leading to further casualties. Therefore, Japan cannot take any particular action except fall behind the US and Europe primarily because Ukraine is geographically distant, but the lack of diplomacy with Eurasia may be the biggest problem.

What are the options for Japan’s Eurasian diplomacy in the future?

We consider the following four options for Japanese diplomacy in the current situation: 1) countering the threats from China and North Korea by strengthening the Japan-US alliance; 2) maintaining ties with the Japan-US alliance while simultaneously working to ease tensions between Japan, China, and Russia; 3) seeking a “bridge diplomacy” in US-China relations; 4) striving to strengthen relations with Eurasia, including Europe, as an indirect means to achieve the above policies.

In practice, options 1 and 2 are being pursued. Whether diplomacy concerning option 2 is sufficient may be debatable, but Japan is attempting to maintain a stance of dialog while taking precautions against China and Russia. The issue lies with options 3 and 4. As a country at the eastern end of Eurasia, located between the two, Japan has emphasized alliances with sea powers and a path of cooperation with the US and the United Kingdom. However, if China, a rival power, expands, and a new balance of power is established, what role will Japan play between the US and China? The worst-case scenario for Japan is a negotiated agreement between the two powers over Japan’s head.

The memory of Kissinger’s secret diplomacy for Nixon’s visit to China, not divulged to the Japanese government in advance, is a recurring theme.

Option 3 is diplomacy in which Japan can substantively demonstrate its presence between the US and China. Nevertheless, it is not easy under the current circumstances; many think it is impossible. This is nothing of the Senkaku Islands and other major frictions between Japan and China that come before the US-China relationship. Rather, given the North Korean missile crisis, I think there is a persuasive view that Japan is strengthening the Japan-US alliance to maintain its security. Some believe that if Japan acts strangely here, it could destabilize US relations. Such an attempt would destabilize Japanese diplomacy, leading to a high possibility of misunderstanding between the two major powers. As this is a wild-card choice, the only choice is between options 1 and 2. Most media and public opinion have settled on these as a safe start.

However, Japan would become a dependent variable if the US and China grew closer or reached a compromise. When the Cold War structure of the US-China confrontation was settled, with limited options for Japanese diplomacy, this was not the preferred international order but an unsafe one. Further, if this is the case, we must consider that it can break down. If the range of options available to Japanese diplomacy at that time was to be expanded, an approach to Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific was essential. The wars in Afghanistan and Ukraine are events that remind us of the importance of Eurasia. Power games backed by military power, mainly those of the US and Russia, will certainly not be the final solution to the problem.

In Eurasia, there is a multilateral framework with leading core countries at the center of their respective regions or spheres of influence. Would it be possible to put all of these into a single, large framework? These regions and multilateral cooperation organizations are not united in the desires of their major countries; there is also considerable frustration in the satellite countries of these spheres of influence. A framework like a “Eurasian Security Community” or “Eurasian Security Council” that includes Japan and South Korea should be preferable. A “collective security framework” differs from a “collective defense framework.” The latter describes cooperation to strengthen defenses against a hypothetical enemy and is premised on hostilities, while the former refers to cooperation to prevent or preempt hostilities. Japan should aim for the former. In Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation (OSCE, the successor to the Cold War-era Council for Security and Cooperation of Europe (CSCE), including Russia and North America) is a security arrangement that has existed since the Cold War. There are questions about its usefulness because it has been unable to mount an adequate response to the Bosnian and Ukrainian conflicts in the post-Cold War era. However, this does not mean that the expansion of a military defense framework (NATO) brought peace; it only led to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

While it is an idealistic view, I believe that Japan should pursue an Indo-Pacific strategy and make a sincere effort to seek a “Eurasian Security Community” and advocate for it on the world stage. Diplomacy acts behind the scenes to support security against the North Korean missile crisis and China’s navigation of the East China Sea. Indeed, linking Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific would be fitting for Japan. As seen with the OSCE, it is highly doubtful that a broad-based security framework would become an effective framework and structure. Nevertheless, a forum where Eurasian and Pacific nations can come together will be essential in the future. Although discussions regarding its realization today sound vague, there was a “Hashimoto Initiative” that intended to achieve this following the end of the Cold War. It will not be easily achieved, but I believe that showing the world its approach would serve to claim Japanese diplomacy to the world. It would be good for Japan to again propose a dialog to this end. While the outcome of such a dialog is important, the continuation of such a dialog is more important. This is because armed conflict can be avoided as long as that dialog continues. Losing channels for dialog or possessing only unidirectional channels is the greatest danger because it paves the way for armed conflict. The diplomatic acumen to persuade other parties and encourage cooperation is important to this dialog. The essence of political realism lies not in the imposition of one-sided ideals or worldviews but diplomatic actions through insight and dialog that make cooperation possible.

(Note) This article is heavily revised from my earlier article yūrashia kara mita kokusai seiji ─ ─ chiseigaku to gurōbarugabanansu no apurōchi [International Politics from the Perspective of Eurasia: Geopolitics and Global Governance Approaches] (JFIR World Review, Special Feature: ima yūrashia de nani ga okotte iru no ka [What’s Happening in Eurasia Today?], Japan International Forum, June 2018

(This is the English translation of an article written by WATANABE Hirotaka, Distinguished Research Fellow, JFIR/Professor, Teikyo University, which originally appeared on yūrashia dainamizumu to nihon [Japan’s Diplomacy in Eurasian Dynamism], Chuokoron-Shinsha, July 2022.)